Based on a resolution adopted in May 2011, the Synod of the Reformed Church in Hungary held a unique meeting on 28-29 September at the SDG Conference Centre in Balatonszárszó in order to discuss issues that fell outside the scope of the Synod's regular meetings. The discussion began with the opening remarks of Presiding Bishop Gusztáv Bölcskei, which focused on evaluating the past, defining the present situation and looking into the future. During the extraordinary Synod, various issues were raised, including the duties of serving in the church, the training of pastors, as well as economic and social questions. Below is small selection of the topics discussed in Balatonszárszó.

Reformed chances and prospects. Written by Ádám Hámori. Published in Confessio, 2011/4

Church membership is gradually diminishing and ageing, there is a high rate of attrition, church buildings are getting emptier by the day, society is turning away from religion – these and similar processes are hypothesized about in connection with religion in Hungary, not only by ordinary church members, but also by countryside pastors who experience such changes. Looking at the vital statistics of recent years regarding the Hungarian Reformed community, the above possibilities do not seem far-fetched at all. Still, according to religious research studies conducted over the last decades, the picture is more complex than that. While religiosity is indeed changing, and the social role of churches has been diminishing in certain areas, in several countries there is an increasing openness towards transcendent and spiritual ideas, and many people are now adopting a religious way of thinking.

In the wake of the fall of Communism in Hungary, and at times even before that, sociologists of religion noted that religiosity was spreading in the countries of East-Central Europe. Not only did these observations clearly challenge the idea of the death of religion, but they also provided ample material for experts to examine the causes and effects of the changes in religion. This material was extended with data collected around the turn of the millennium, which indicated another slow decrease in religiosity in several countries, including Hungary after the period of the fall of Communism. At the same time, churches in ex-Socialist countries – formerly staying in the background or suffering from state repression – regained a significant role in society.

So on the one hand, these tendencies are far from homogeneous and do not all point in the same direction. On the other hand, the situation of Hungary is not unique in Europe, although it is not completely identical with that of any other country either. From the point of view of the sociology of religion, the question is what accounts for international differences, apart from the obvious fact of religious change. By finding the answer to this question, one can reveal the social processes that have an impact on religion and churches.

Below is review of tendencies regarding the changes in European religiosity, mostly relying on the data of the European Values Study (EVS). The review only encompasses a sample of tendencies, with the aim of inspiring further thoughts and discussions. This is followed by a basic introduction to the three main theoretical frameworks used for the interpretation of changes, which used to determine and still determine the sociological attitude towards religion. In the subsequent part, a handful of considerations are offered to discuss whether these theoretical frameworks are suitable to discuss the "church religiosity" of the Hungarian population and the evaluation of the situation of the Reformed Church in Hungary. The empirical support of these considerations will be the task of later research studies. Finally, with the aim of providing a potential direction for these studies, some practical implications of these considerations put forward.

The fact and extent of the decrease

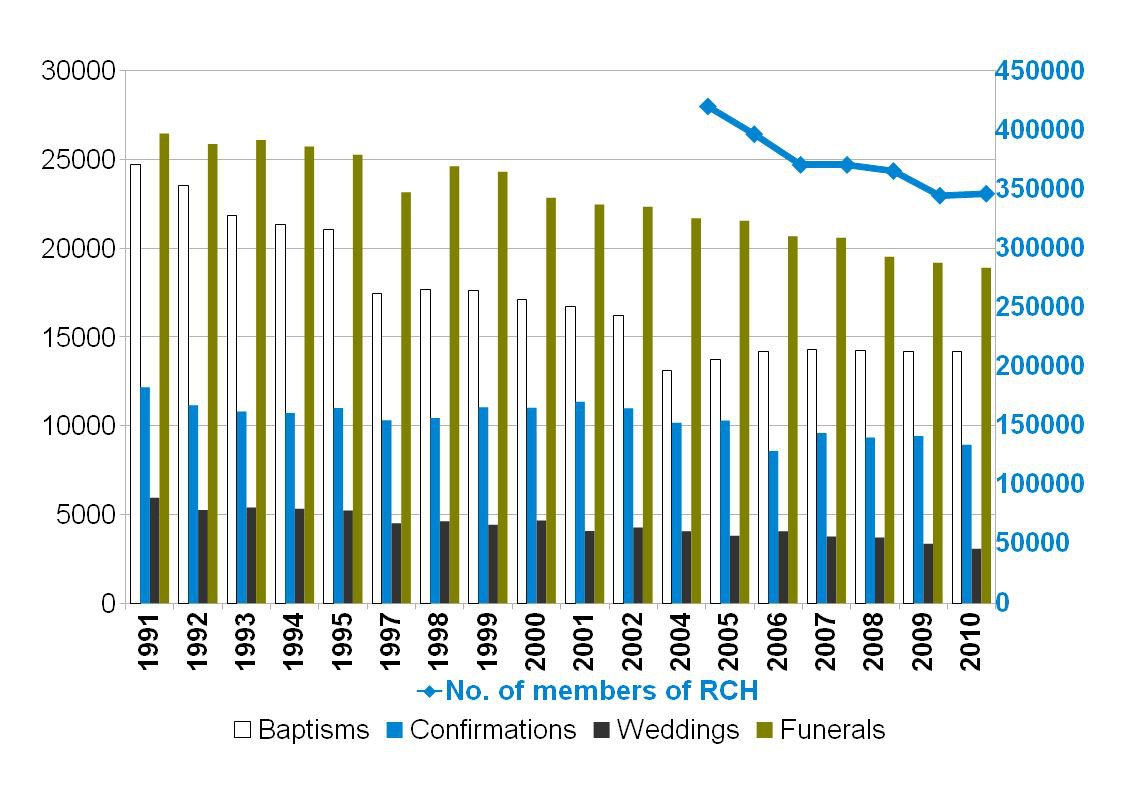

Church statistics have long and undeniably warned of the decrease in the size of the Reformed Church in Hungary in terms of numbers. At the time of writing the present article, aggregated national data is available from 1991 on the number of baptisms, confirmations, marriages and funerals – except for the years 1996 and 2003, and we have had information on the number of church members since 2004. These can be seen in Figure 1, which shows that the number of baptisms was lowest in 2002, after which came a minor rise, and over the last few years it has been stagnating. This is most probably due to demographic reasons (members of the second so-called "Ratkó generation" reached child-bearing age and started having children).

The steady decline in marriages and especially funerals, on the other hand, seems to indicate value-related causes. Marriage rates are falling, according to Hungarian population statistics, although this would not necessarily affect church weddings to such an extent: research studies show that practising church members have a greater tendency to marry than the general public, and alternative forms of family are preferred by the less religious (Pongrácz – Spéder 2003). It is possible, however, that the uncertainty that goes hand in hand with globalization, which influences the decisions of those reaching a marriageable age and also the transitions between different life stages, has an impact on both church-going and non-religious youth (Blossfield – Mills 2005). Turning to the decrease in funeral rates, the well-known fact of ageing both among church members and Hungarian population in general would logically mean that the number of funerals is going up. (Resolving such contradictions would require further research.)

Figure 1

The main vital statistics of the Reformed Church in Hungary

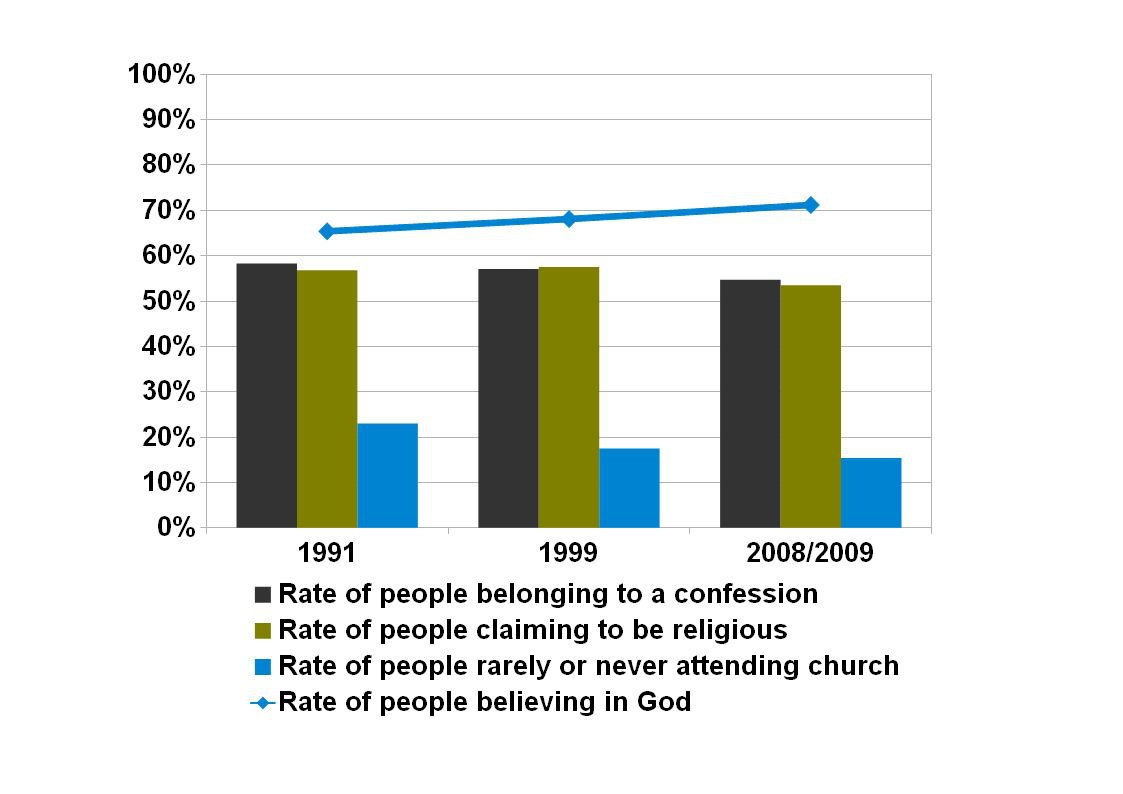

The results of the European Values Study regarding the adult population of Hungary illustrate the direction and complexity of the changes. Figure 2 shows that regular church-going has declined the most visibly: while in the 1991 statistics 23% of respondents answered that they go to church at least once a month, three years ago this figure was only at about 15.5%. Other indicators of religiosity reflect the same tendency: the number of those who consider themselves religious, as well as the number of people belonging to some denomination have also declined, although to a lesser degree. These are somewhat contradicted by the fact that the number of those who believe in God has risen over the last two decades: from 65.4% in 1991 to 71% in 2009.

Is this turning away from practising religion only visible in the churches of Hungary? We get a more nuanced picture if we examine the results of the European Values Study in the international context. Let us have a look at the frequency of church attendance – or more precisely, the lack of it –, as well as the situation of religious identity, denominational affiliation and belief in God. (We decided to include in our analysis only those Western European Protestant countries and East-Central-European post-Socialist countries involved in the EVS study regarding which there was suitable data available for the whole period examined.)

Figure 2

Changes in the main indicators of religiosity in Hungary between 1991-2009.

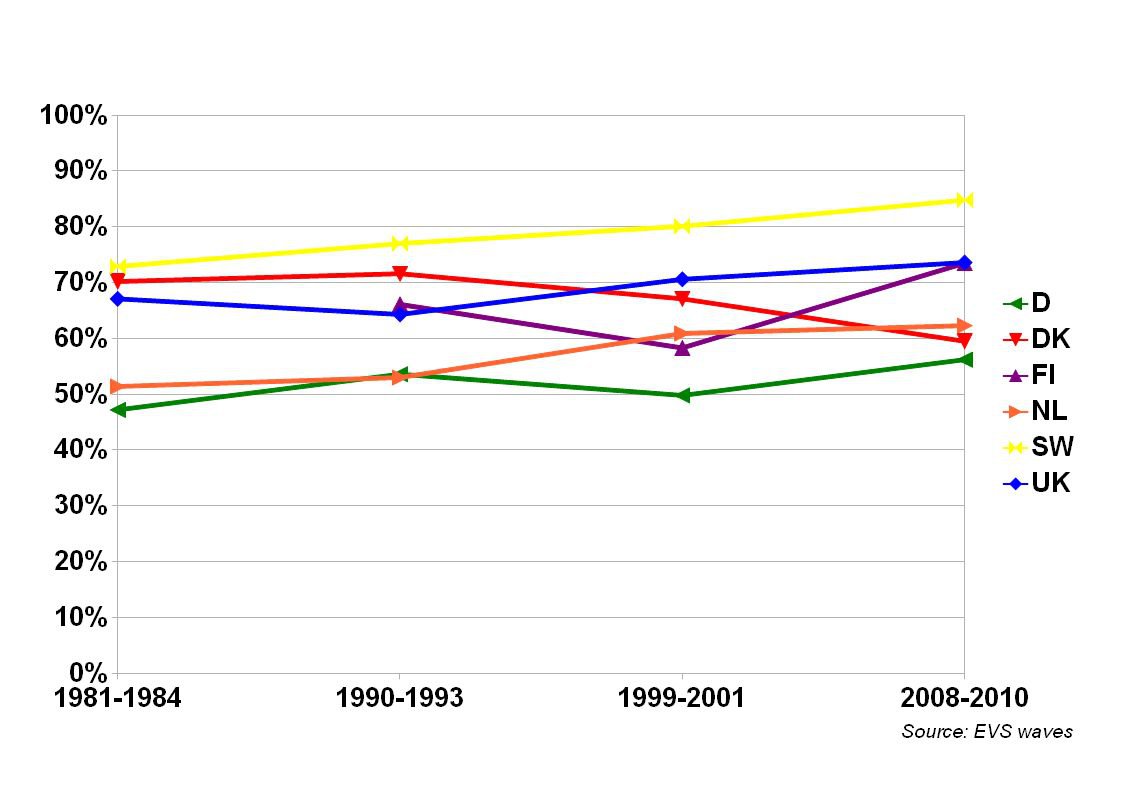

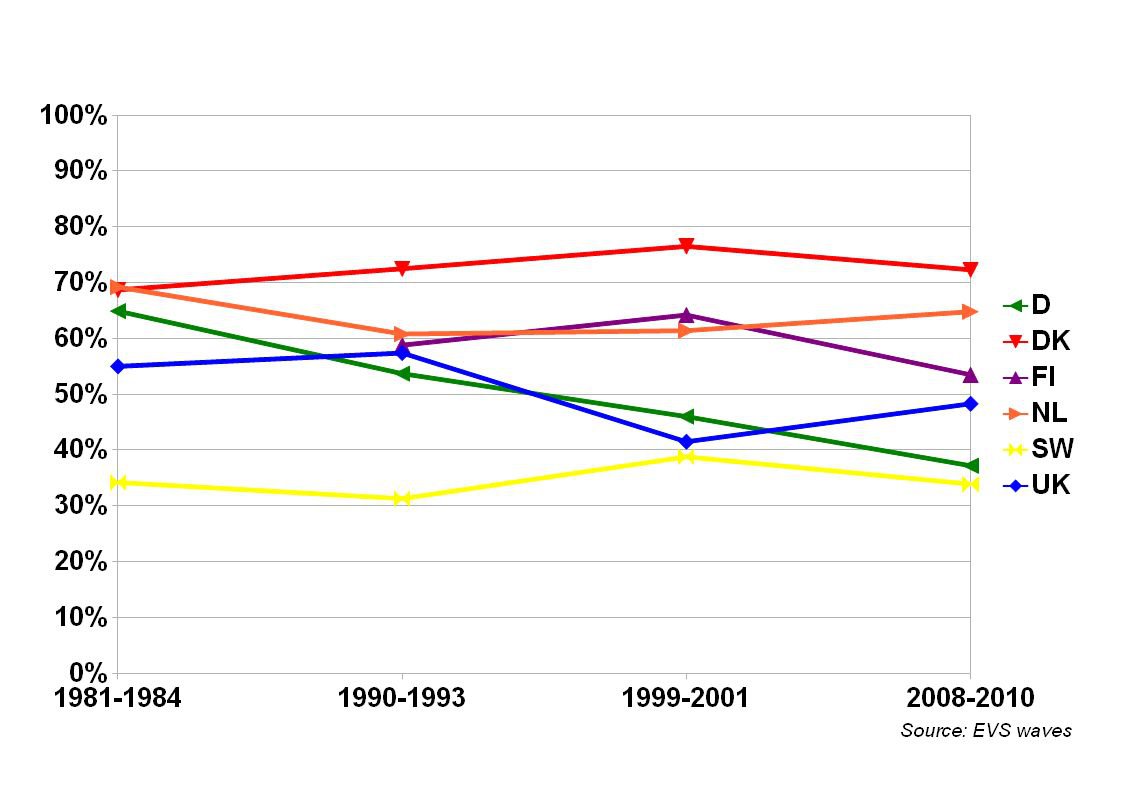

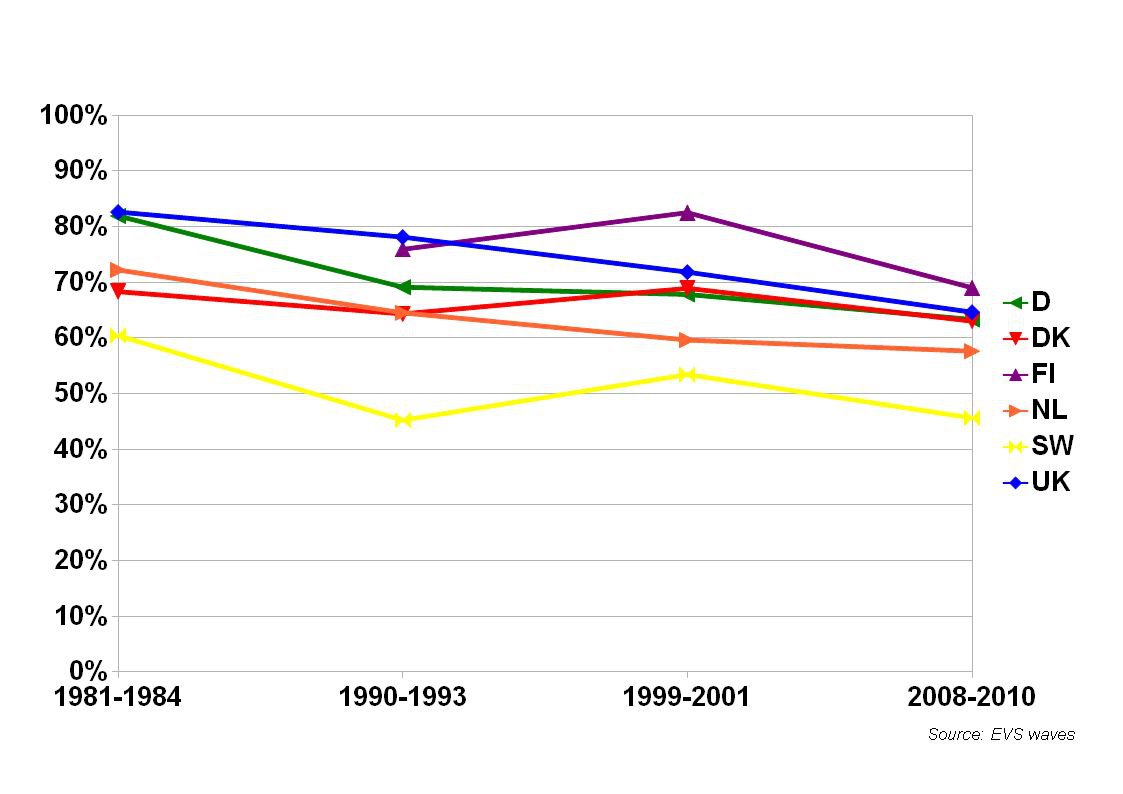

According to Figure 3, institutional religious affiliation is falling all around Europe, but to varying degrees. In Western European Protestant countries, there has been a rise in number of those who never of hardly ever attend church (Denmark is a peculiar exception). The rise is especially dramatic in Sweden, where the extent of non-religiosity had already been high. By now it is true of all the countries examined that the people who hardly ever or never attend church constitute a majority. In comparison with them, Hungary is somewhere in the middle of the list, but staying away from church has also shown a rising tendency here.

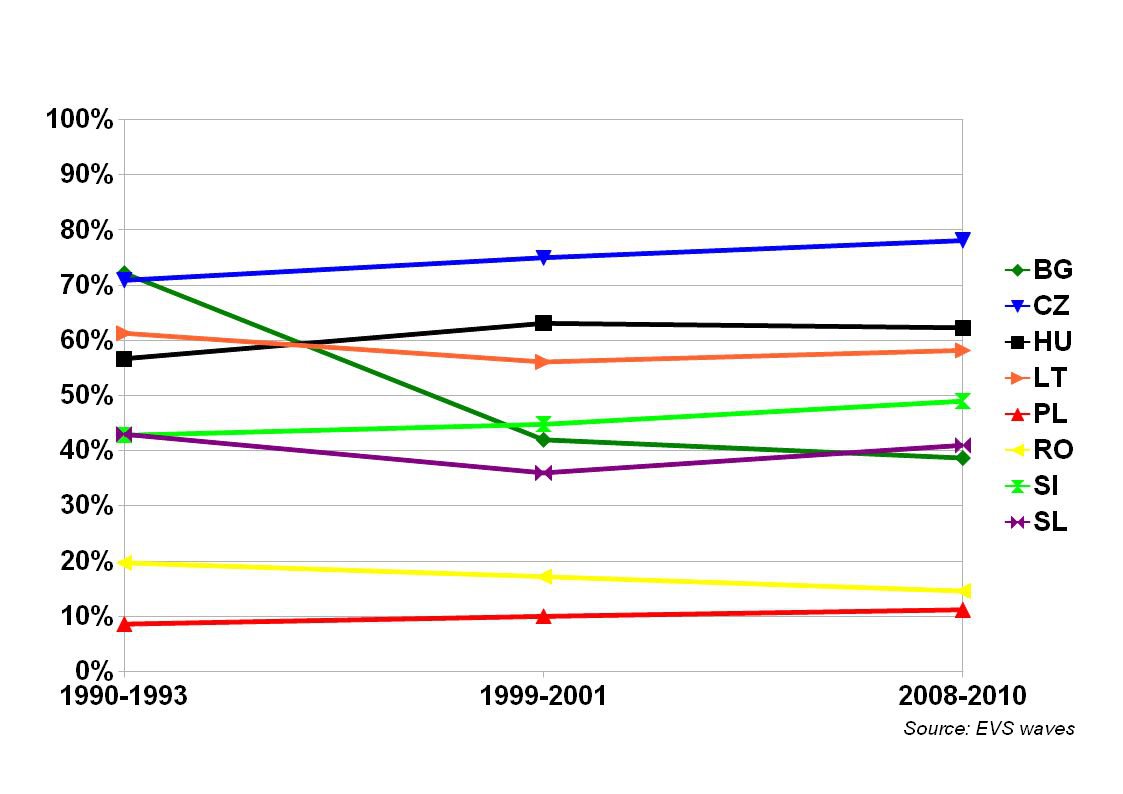

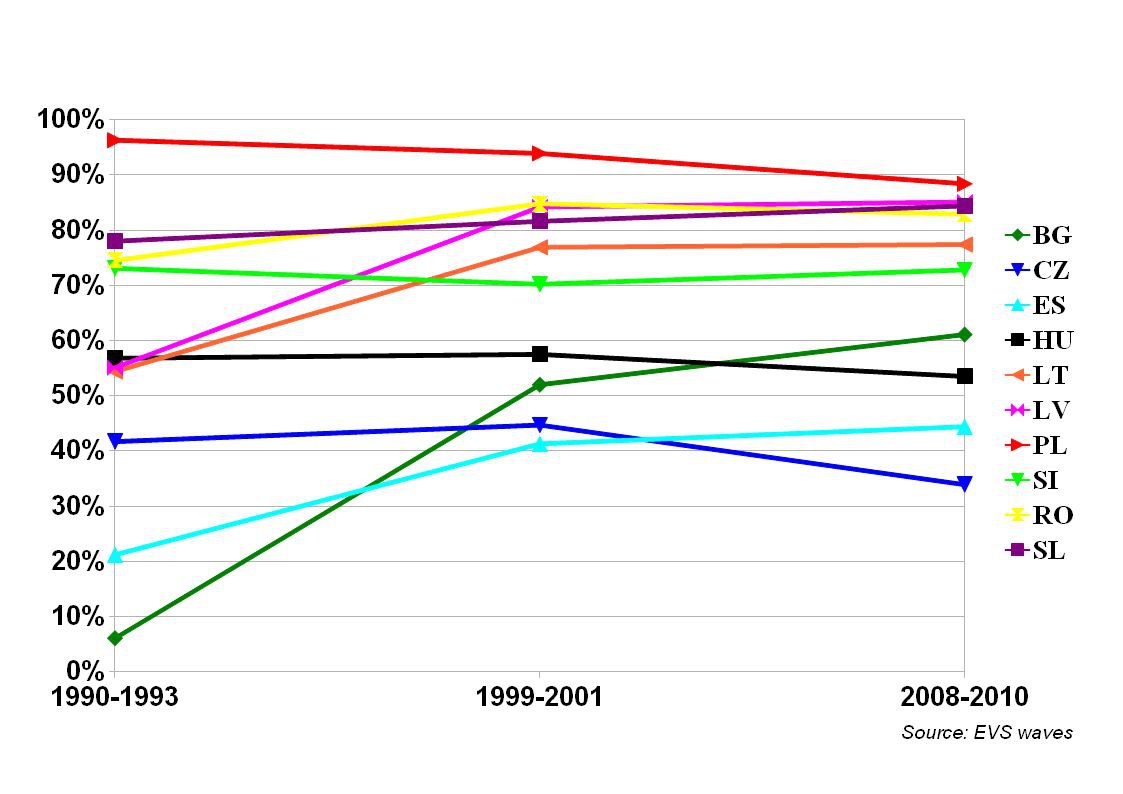

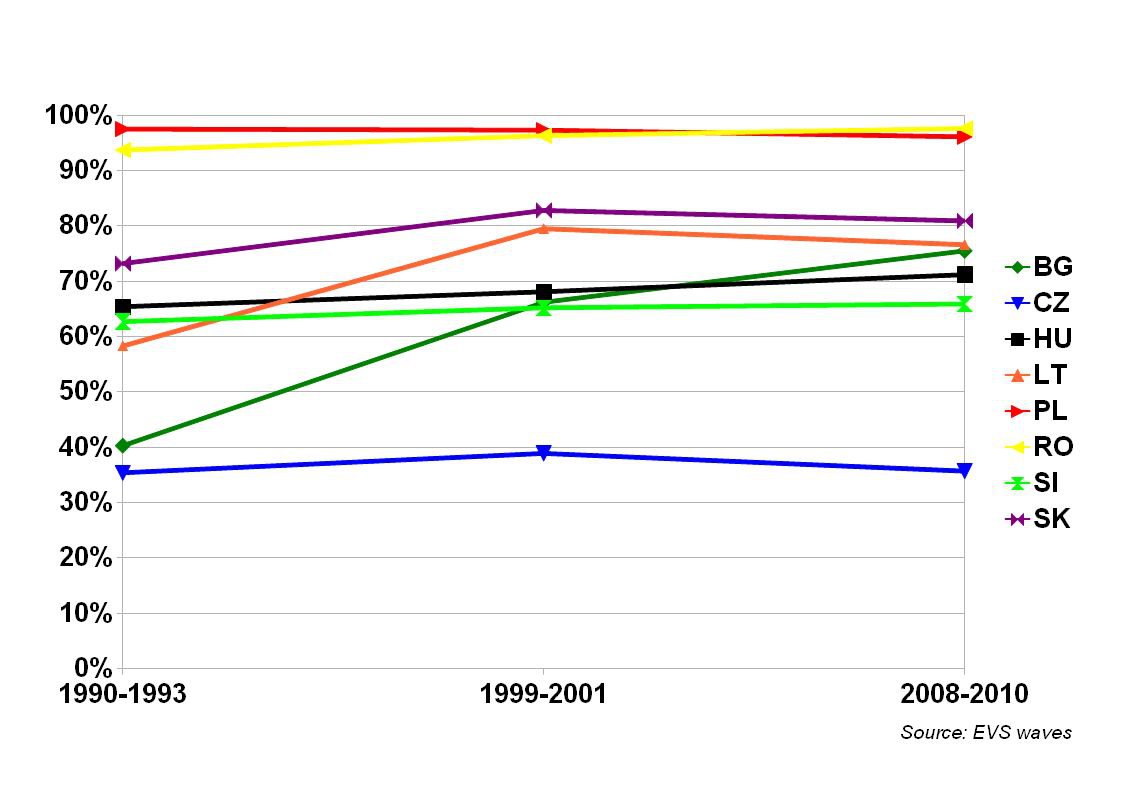

The data featuring in Figure 4 suggests that since the turn of the millennium there has been a slow rise in the number of those who hardly ever or never take part in church services in most East-Central-European countries. Still, there are significant differences between individual post-Socialist countries. The above-mentioned rate is lowest in Poland and Romania; in the former, there has been a slight increase, while in the latter a decrease in the number of those who hardly ever or never attend church services. In Bulgaria, we can see a dynamic rise in terms of practising religion in an institutional form. In this respect, Hungary has one of the worst rates.

Figure 3

The rate of people who hardly ever (less than once a month) attend church services in some Western European countries and in Hungary between 1981 and 2010.

Figure 4

The rate of people who hardly ever (less than once a month) attend church services in some East-Central-European countries between 1991 and 2010.

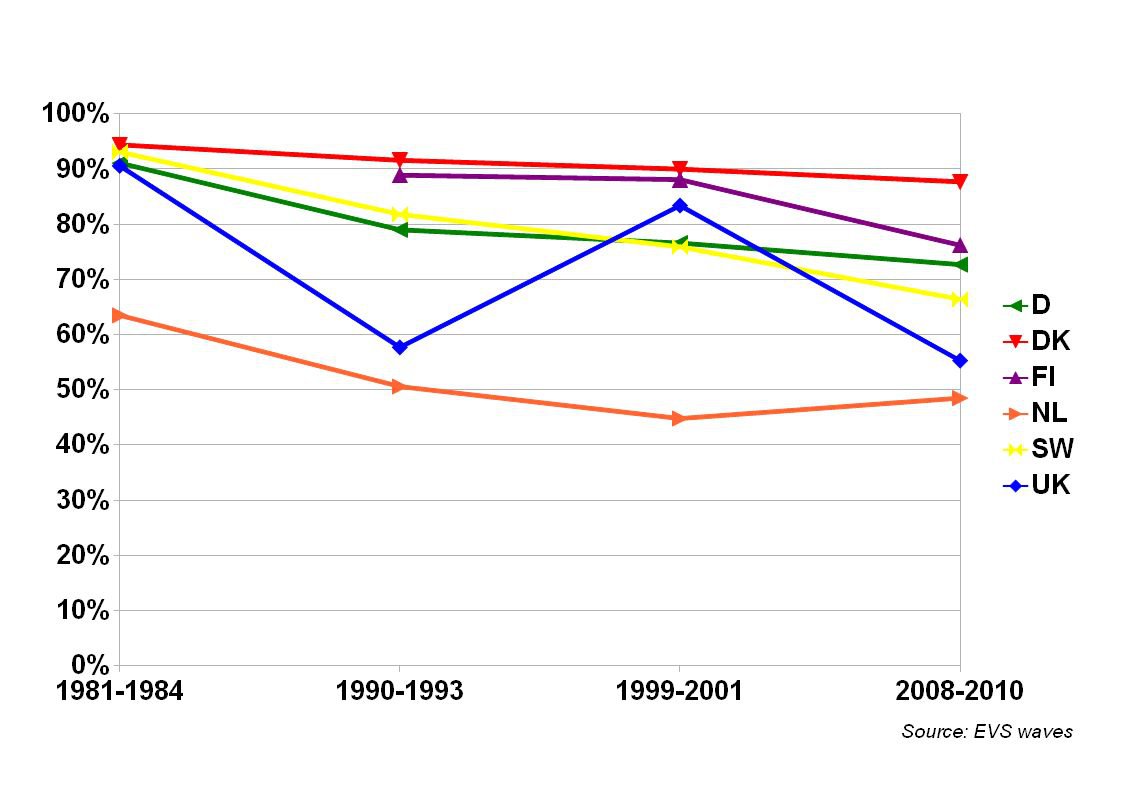

Figure 5

The rate of people who consider themselves religious in some Western European Protestant countries and Hungary between 1981 and 2010.

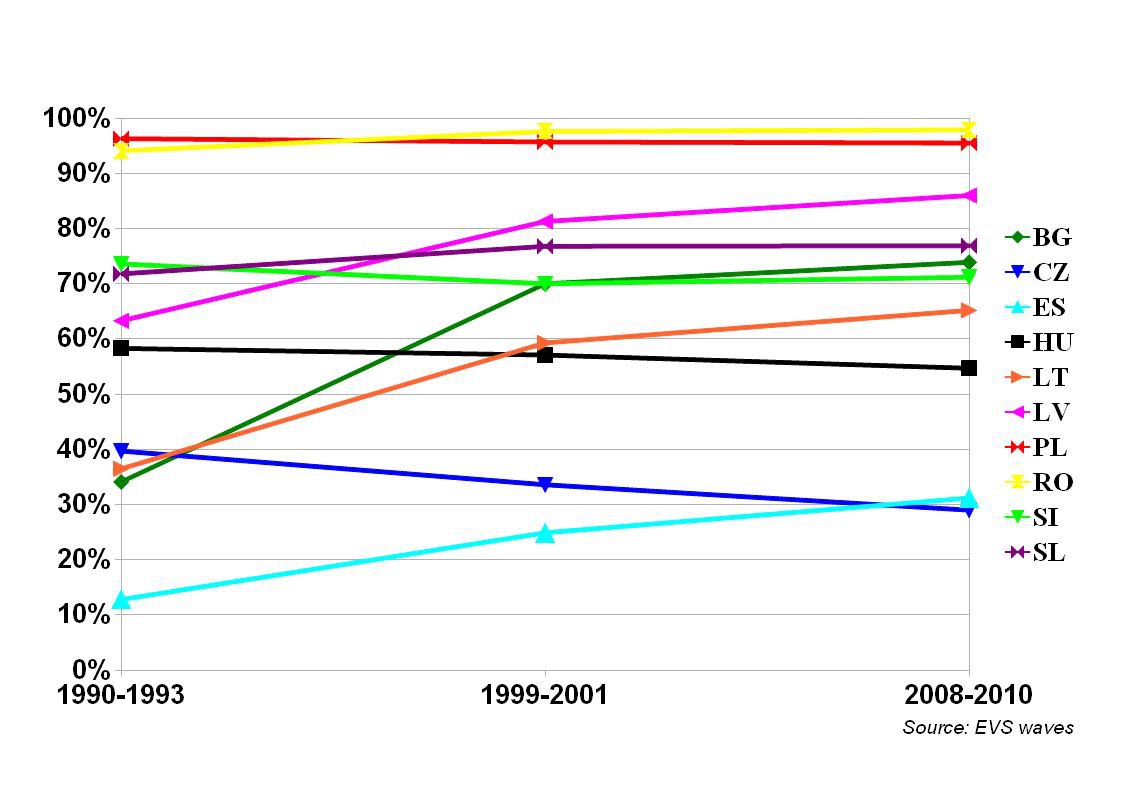

Figure 6

The rate of people who consider themselves religious in some East-Central-European countries.

The hypothesized decline of religiosity is also expressed on the level of individual self-identity. Over the last 30 years, there has been a fall in the number of those who consider themselves religious in several Western European countries. This fall is especially dramatic in Germany, while in the case of Denmark and the Netherlands it is not steady (Figure 5). Looking at East-Central-European countries, we can see that the traditionally most religious Poland has experienced a fall in the number of religious people; in Slovakia and Romania there has been a slight rise, while the rise in Bulgaria has been exceptional (Figure 6). The rate of religious people in Hungary is among the lower ones in this comparison, and – in contrast with the other East-Central-European countries – the rate is going down.

It is important to consider, however, whether people experience their religious affiliation within the framework of a certain denomination. According to the figures of the European Values Study regarding Western European countries, the number of people belonging to a denomination is lower today than it was thirty years ago (Figure 7). At the same time, the situation is quite the opposite in East-Central-European countries: apart from the plummeting rates in three countries – Hungary, the somewhat more religious Slovenia and the Czech Republic, which is generally regarded as non-religious –, the countries show a steady rise in the number of people who claim affiliation to a denomination. The rise is especially dynamic in Bulgaria and Latvia, and even Estonia – which seemed to be mostly non-religious in previous studies – overtook the Czech Republic in terms of denominational affiliation (Figure 8).

Figure 7

The rate of people claiming denominational affiliation in some Western European Protestant countries and in Hungary between 1981 and 2010.

Figure 8

The rate of people claiming denominational affiliation in some East-Central-European countries between 1991 and 2010.

Nevertheless, religious affiliation and the institutional practice of religion, or in other words, church affiliation is not necessarily in direct correspondence with the acceptance of religious content or faith. Still, the rate of those who believe in God follows a similar dynamic in most Western European countries to that of denominational affiliation, religious identity and church attendance. The change is yet again more complex in the case of East-Central-European countries; at times it differs from Western European patterns, at other times from other indicators of religiosity. Accordingly, in the Czech Republic the number of those who believe in God is low and falling, while the same figure is dynamically rising (from a low starting point) in Bulgaria and Latvia. Among the countries compared, the ones with the highest number of believers are Poland and Romania, while there is a rising tendency in Hungary – in contrast with the falling figures of the frequency of church attendance, denominational affiliation and religious identity.

So far we have compared the changes regarding the entire (adult) population of countries. When the religiosity of a society is examined, the analyses conducted in the sociology of religion deal extensively with the significance of demographic and socio-economic factors influencing individual religiosity. The limitations of the present article do not allow for the examination of each and every context or the detailed analysis of the differences between countries from these aspects, but it is worth looking into the situation of Hungary's religiosity within the contexts of age and settlement type.

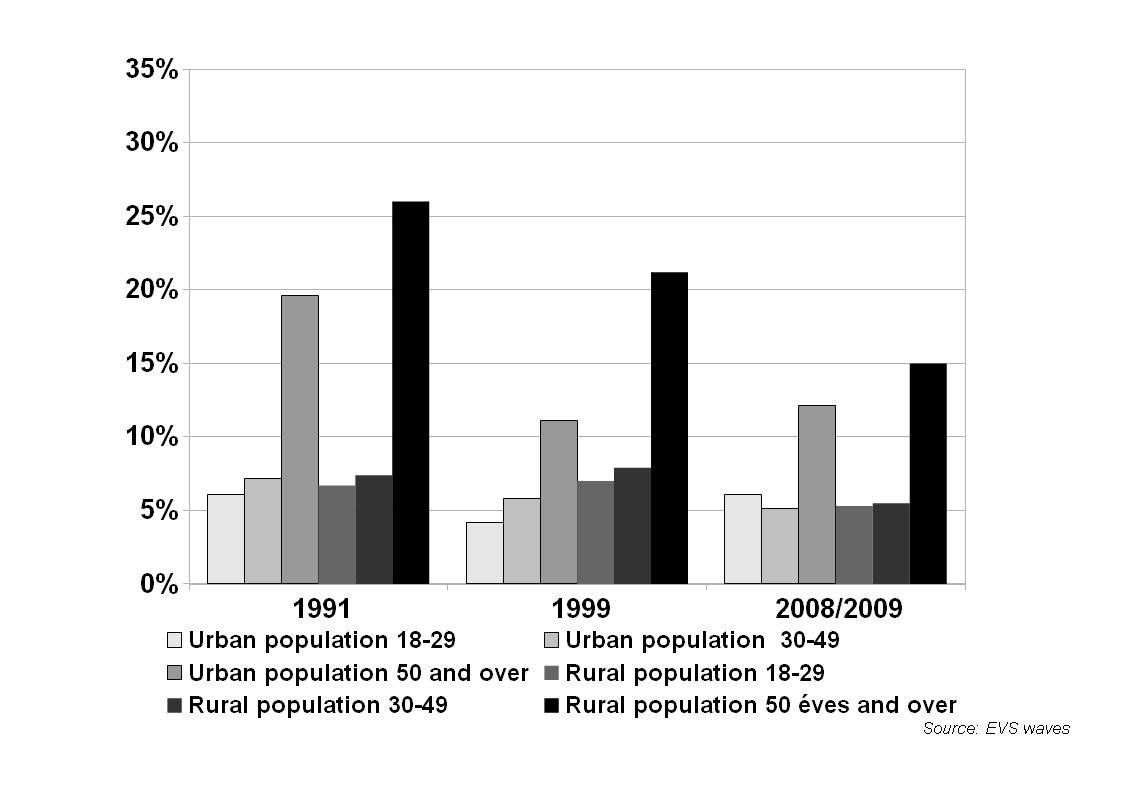

Through the analysis of the EVS data, Miklós Tomka has pointed out that there is a sharp dividing line between the religiosity of those over 50 and that of the younger generations, and it is also important whether they live in an urban or a rural environment.

Figure 9

The rate of people who believe in God in some Western European Protestant countries and Hungary between 1981 and 2010.

Figure 10

The rate of people who believe in God in some East-Central-European countries between 1991 and 2010.

When we examine these two factors together, we can state that between the beginning of the 1990s and today, in all four groups – young and old city-dwellers, as well as the young and old rural population – the number of those who practise religion has fallen. The most dramatic decline has occurred in the group of the elderly rural population: the number of those who practise religion has fallen by roughly a half. As a result, the entire religious population seems to be getting more even in terms of age and place of living, and it is no longer true that the most typical religious group is that of the elderly rural population (Tomka 2010).

In order to examine them, we divided the respondents of the EVS lines into three age groups (aged 18-29, aged 30-49, 50 or older), and we separated those who live in settlements with a population under 20,000 from those who live in settlements with a larger population. Figure 11 shows the rate of those who claim to go to church once a week or even more frequently. As we can see, there is a significant drop regarding both the urban and the rural elderly population, although in the last 10 years there seems to be a rising tendency regarding the urban 50 or over population.

Figure 11

The rate of people who attend church at least once a week within the age groups of urban and rural populations in Hungary between 1991 and 2009.

At the same time, the much lower rate of the younger generations has been stagnating. Although the data from 2008 indicates a slight increase in the youngest urban population, the data recording only included the adult population of Hungary. The third wave of the representative national Youth Study conducted in Hungary at the same time period warns, however, that on the whole this age group also shows a significant reduction in religiosity and the practice of religion. The reduction is strongest in the age group (15-18 year-olds) that was not included in the Hungarian results of the European Values Study (Hámori – Rosta 2011).

Secularization?

The most influential theory of the last two centuries, which has been used to explain the religious change that took place after modernization (basically the Industrial Revolution), is the so-called secularization thesis (Pollack 2009, Casanova 2004, Dobbelaere 2002). Although this explanatory model never developed into a separate and unified theory, according to certain critics (Tomka 2000, 2002), the gist of it is the following: as a result of the birth and spread of modernism, religiosity – first and foremost Christianity, but also every worldview based on irrational, transcendent ideas – inevitably withdraws from all areas of life, giving way to the scientific-rational worldviews which spread inexorably. The religious attitude of individuals gradually fades away, and parallel to this – to be more precise, some say it is the cause of the worldview transformation, while others say it is a result – church structures lose their former power and influence over national political systems as well as over the everyday lives of individuals.

The two main reasons for dismissing the secularization theory are the past and the present. Stark (1999), summarizing the findings of other studies, concludes: the frequency of church attendance and the rate of active church membership has never been significantly higher than today, and religious decline did not begin with modernization. He adds that there have naturally been minor fluctuations in the spread and influence of religion. Still, a series of historical studies have proved that a so-called "religious Golden Age" – when the majority of the Europeans were supposedly active followers of Christ – only ever existed in the heads of those who welcomed the idea of churches disappearing and those who wailed over the death of religion. Contemporary notes and regulations suggest that in the early Middle Ages even the clergy was vastly ignorant of the teachings of the Catholic Church, there was a lack of Latin knowledge that would have been necessary for the liturgy, and the majority of the general population (peasantry) seldom took part in church services. The misconceptions are caused by the enormous and impressive church buildings, as well as the amazing works of art and influential scientific achievements connected to church culture. While these prove the wealth and commitment of the church-affiliated powerful elite, after ancient times there is hardly any evidence that the church, which was intertwined with worldly power in many ways, made systematic efforts to convert the general public (who were not much impressed by the liturgy delivered in poor Latin either).

To refute the other hypothesis of the secularization thesis, namely the disappearance of religious thinking, one only needs to observe the statistics presented earlier. In the first decades of the 21st century, religious ideas are still of great significance in European culture, therefore we cannot talk about the disappearance of religiosity by any means. This is not to say, however, that religiosity has not changed at all. It is obvious – at least in Europe – that the social and political role of churches is completely different from that of earlier centuries, but they still have not lost their political significance. Doubtless, the historical, religious and political culture of individual countries greatly determines the current situation of churches (note by Rosta). In the United States, where there is a strict separation of state and church, and society is characterized by a complete freedom of religion, 95% of people today claim to believe in God, and four-fifth of them say they are religious and affiliated to some denomination. Outside European culture, religion seems to enjoy unparalleled social and political popularity – the terrorist attacks motivated by Islamic extremism are the most shocking, but not the most typical examples for this. Modernization, therefore, is not necessarily followed by secularization.

Individualism?

While the openness towards religiosity seems to be as strong as ever, the fact that many are turning away from practising religion in an institutional form requires an explanation. It was Miklós Tomka who developed a typology in the 1970s to examine religious identity, which has since been used in international studies (Tomka 1997; 1994; 1973). On the basis of this question – which enables us to distinguish between groups of those who follow the teachings of a certain church and those who experience religion in their own way, as well as the groups who reject religion to varying degrees – shows that over the last decades there has been a reduction in "church religiosity" and a rise in individual religiosity that is not connected to any church or denomination.

The findings rhyme with the model used in the sociology of religion known as "religious individualism" (Rosta 2008, Luckmann 1991, Hervieu-Léger 2004), according to which people increasingly experience their religiosity by leaving behind religious communities, in their own private lives, on the basis of worldviews of their own making, often taking bits and pieces from the teachings of various religious traditions without their original context and even modifying them. The result is a so-called "do-it-yourself" religion. Communal religiosity is transformed from a social phenomenon into individual faith, and consequently the social role of religious communities and institutionalized religiosity becomes less significant, and the influence of the traditional teachings diminishes. Researchers also refer to this situation as "believing without belonging" (Davie 1994, 1990). Studies in the sociology of religion suggest that the various dimensions of religiosity – religious identity, the religious beliefs actually accepted, the forms of practising religion, the value system partly influenced by religion, as well as the demographic and socio-economic factors that used to be in strong correlation with these – become separated from each other.

The theory of religious individualism does well describe the process of change on the level of the individual, and highlights important consequences from the point of view of churches and religious institutions. However, it fails to say much about the social processes or the transformations in religious institutions that could account for these changes; just like the secularization thesis, it merely states the fact of change in the spiritual needs of individuals, in their "religious demand" – noting that one of the prerequisites for this change is religious pluralism, i.e. when people have the freedom to choose from various forms of religion.

Competing churches?

As an alternative to the secularization thesis, a new theoretical framework has become dominant since the 1990s in the sociological thinking about religion: the theory of religious market and religious economy. In this theory the space defined by churches is described as an area of cultural consumption, in which the prevalent rules are similar to market mechanisms. On the basis of the theory of rational decisions, individuals – both current church members and potential future ones – are viewed as consumers capable of making their own choices, who pick from the available supply of churches, and constantly weigh up the investment expected of them in a denomination or community, and the rewards they receive in return in terms of religious experience (Sherkat – Wilson 1995; Sherkat – Ellison 1999).

According to this theory, just like economic changes, religious ones can also be described with the help of models. Churches, similarly to corporations, manage their operations by using certain resources, the donations and voluntary services of their members, which they turn into so-called "religious commodities", offering them to those willing to invest into the given church from their own personal resources – their wealth, time or expertise (Iannaccone – Olson – Stark 1995). The issue of "free riding" has been analyzed by numerous researchers – the phenomenon when someone wishes to access the commodities of the church without any personal investment that could be expected of them (Iannaccone 1994). Although several parts of this theory have not been sufficiently developed yet, such as the question of what constitutes religious commodity, it is still a useful tool for sociologists to explain and more importantly, measure various change processes of religiosity. Also, it could help churches to clarify certain institutional anomalies that stand in the way of the appropriate management of resources, work against growth or even threaten to destroy churches themselves.

An important statement by researchers belonging to this theoretical school is that the free competition of denominations and religious groups – free in the sense that it is not distorted by legal regulations, state privileges, or a state church status – ultimately leads to the growth of the "religious consumption" of society, in other words, an increase in the number of those who belong to a denomination and attend church services. While previous theories stated that widespread religiosity can only be possible if there are conservative and strict churches that enjoy an exclusive status in a given society, and denominational diversity results in the relativization of fundamental religious values and people's turning away from religiosity, the theory of religious economy has pointed out that the competition that arises from diversity and the removal of the regulations distorting the religious market mean a stimulus for institutionalized religions (Iannaccone 1991). This is so because they are forced to make an effort to win over the highest possible number of believers, to keep or even extend their membership, as – in the absence of state privileges and public support – their survival is entirely dependent on the donations and voluntary services of their members. Secularization theory, on the one hand, analyzes religious change from the point of view of "religious demand" and explains the diminishing influence of churches by the individuals' loss of religion; the theory of religious market, on the other hand, does the same from the point of view of "religious supply".

This influential theory of postmodern sociology of religion has been underpinned by empirical data from the United States of America, pointing out that previously, when the religious market – which was under state control – of most states was exclusively controlled by one denomination each, the number of those who actively practised their religion by attending church was significantly lower than later, when the former privileges were abolished, and there were no more limits to the appearance of new denominations and sects. Already in the 18th century, the beneficial effects of the denominational competition that developed in the free "religious market" were discussed by the greatly influential ethics philosopher Adam Smith, whose idea of a self-regulating free market became the centre of modern economy (Smith [1759] 1982, Iannaccone 1991). Naturally, not everybody is a winner when the religious market is liberalized: the churches that previously enjoyed a privileged status lose, while the new sects and small communities entering the market benefit from the new situation – this has been observed in other places as well, like in East-Central Europe (Iannaccone – Finke – Stark 1997, quoted by Iannaccone 1998).

As we have pointed out above, a prerequisite of religious individualism is the pluralism of religion, without which no free religious market could come about. The two theories, however, are not in contrast with each other; the more appropriate approach seems to be that individualized religiosity (being religious "in one's own way", do-it-yourself faith) appears as an equal alternative to denominational or church religion (Tomka 2011, 2002) – as a rival "do-it-yourself" product among the supply of the players of the religious market, the "ingredients" of which are easily available to anyone from sources not controlled by churches.

It is clear that these theories do not wish to replace other – theological, cultural, historical – interpretations of religiosity or churches, and they are not exclusive in the sense that other sociological interpretations of religion and church do co-exist with them. Still, the well-known and widespread theoretical schools of thought presented above provide a relevant framework of thinking with their own ideological background and special methodological implications. In any case, the obvious question arises whether the theoretical approaches that more or less aptly describe phenomena in Western Europe and the United States can be used to explain the Hungarian situation of religion, and if yes, to what extent.

Another "Hungarian peculiarity"?

One can assume that in Hungary – especially but not exclusively among the older generations – there is a traditional attachment to religiosity and traditional (so-called "historical") church communities, which can be described with the concepts of inherited family patterns and folk church religiosity. In this segment of religiosity, secularization is well-defined: as we can see in Figure 11, the elderly (50 or older) generation represents a group that is less and less religious as time progresses. This is connected to the differences in each generation's early socialization (Rosta 2007). It is also characteristic of other European countries that when the population representing traditional values dies, it is replaced by an ever less religious population (it "ages" into an older age group) whose upbringing was less defined by religious values (Inglehart 2008, 1977). The significant fall in religiosity is not offset by the life-cycle effect, i.e. the tendency for some people to get closer to religion as they grow older (Tomka 2010). On the whole, it can be stated that while there is a tendency of secularization on the level of individual piety (Tomak 2011), this is mostly due to demographic factors, not to cultural and value system influences, as modernization itself does not necessarily override the embedded religious values.

On the other hand, it is increasingly true of the religious market in Hungary that – especially, but not exclusively among the younger generations – there is a growing popularity of conscious choice based on rational decisions. In comparison with traditional religiosity, the main difference is not like in the United States, where current church members and potential ones still outside denominations consciously pick from the array of religious commodities offered to them. Although one can find such examples in Hungary as well, this kind of picking or even switching has not become common. (The possible reasons for this will be analyzed later on.) In Hungary, the "conscious consumers of religion" are characterized by the fact that they do not approach faith as something inherited, a continuation of family tradition; instead, they make an individual, conscious decision to become committed to religion, and this influences every aspect of their lives, including their other decisions, and the result is a much stronger bond (Tomka 2009).

The appearance of such a slowly increasing religious core makes it necessary for us to analyze the religious change in Hungary from the point of view of the religious market theory, especially because the religious situation in Hungary – and in ex-Socialist countries in general – was greatly influenced by the fall of Communism, the disappearance of the former political-ideological restriction of churches. In the early 1990s it was surprising to see a revival in the interest towards religion in these countries. The changes in the political environment alone could lead to the spread of religiosity in the new democracy, as people – to use the terms of the sociology of religion – were now able to seek ways to satisfy their religious needs without having to worry about state retribution (Tomka 1990). However, as it has been stated before, the theory of religious market does not try to explain the changes from the point of view of demand – those interested in religion –, but from that of supply, i.e. church institutions and religious communities. In our case the explanation is that with the fall of Communism the factors that stood in the way of the development of a free religious market were eliminated, and the institutions became free to compete with each other in order to get new members.

There are, however, at least two obstacles that prevented the birth of free competition cited in the theory of free religious market. One of them is the presence of traditional religiosity, the social embeddedness of traditional "big" churches which had an undeniable advantage. This embeddedness means that a significant proportion of society is "involved" in one way or another, meaning that their immediate (family) surroundings suggest an obvious denominational choice for them: following the example of their parents (on the significance of this, see further Sherkat 2001). Although there are measurable consequences in the case of the young generation to the imperfections of passing on values from one generation to the next (Hámori – Rosta 2010), the popularity of sects and cults has been far less significant in Hungary than in the previously presented example of the United States (Finke – Guest – Stark 1996, Finke – Stark 1988). Still, the elimination of the former ideology-based repression after the fall of Communism can be interpreted as the "liberalization of the religious market", which may have led to a temporary and limited competition among churches, prompting them to make more efforts to address society. The short-lived religious awakening and the growing interest in religion are partly justified by this theory, but it could also be used to explain the recent fall.

The second obstacle that stands in the way of unhindered competition among denominations lies in the largely institutionalized nature of big churches, and in their significance in public life. On the surface this seems to mean nothing but greater publicity in comparison with smaller churches and sect-like communities, but the effect is more complex than that. Miklós Tomka has noted (2000) that a high level of institutionalization works against the sustainability of the original religious experience and also the ability to mediate it:

"The more institutionalized a religion is, the more likely it is to fall behind culturally. This falling behind is not merely a form of cultural conservatism, but the distancing from the questions of the new era result in the inadequacy of answers. The harmony between current questions and old answers (or answers expressed in old cultural forms) is broken. The system of religious culture, no matter what philosophical harmony it reflects, gradually loses its significance in everyday contexts. It increasingly fails to address the issues that people are interested in. People can no longer find an encounter with Wholeness, or in more simple terms: find answers to their questions. They see less and less point in participating in religion. So they stop participating. The institution's inability to change kills the (given) religion. The history of religion has recorded many religions that disappeared, and several of these have been victims of their own institutional rigidity."

The institutionalization of a religion, however, is not reversible in the case of traditional big churches. Indeed, such a process is inevitable, as it is only this way that churches can fulfil the functions that ensure their presence in society, which have become their special responsibilities. Therefore while churches are unable to mediate the original message of religion due to their highly institutionalized structure (although institutionalization does not always prevent this possibility in local, communal or interpersonal relations!), they also gain new channels of communication, through which they can reach a greater proportion of society. Consequently, this "dilemma of institutionalization" does not necessarily lead to the loss of religiosity on the level of society, but may amplify the similar effects of other processes.

From the point of view of institutionalization it is important to note that the so-called "historical" churches in Hungary have also adopted an influential role in running institutions (Tomka [1998] 2008). Needless to say it would be impossible to maintain an extensive system of educational, health, nursing, social and cultural institutions exclusively from the donations of church members, especially when the social status of members restricts their ability to donate. Churches, having lost their wealth required for self-sustenance during the nationalization process that followed the Second World War, are forced to rely on primarily central state budget resources, and they also receive significant financial support from the state to maintain their religious activities. It follows that these churches do not have the financial incentive to engage in the competition for new supporters under circumstances similar to those of market competition, using the tools of the market – unlike smaller communities who do not enjoy the same amount of central state support.

Finally, a related issue to discuss here is the relationship of churches and politics. In the (mostly Orthodox) countries east and south of Hungary, "state churches" are a typical phenomenon, where – generally speaking – a single church (or a small number of churches) enjoys a privileged status in the eyes of the state, and gains more significance than other denominations. From a legal point of view, Hungary has been characterized by a liberal religious structure since the fall of Communism. In actual political practice governments (and not just those claiming to represent national values) have devoted special attention to historical churches – which has never been a legal category –, making use of their symbolic legitimizing function. Although the uneven situation was justified by the size of churches' membership, their traditions and their social responsibility, the status of traditionally big churches can be interpreted as a "quasi-state-church" status. The new church law, in line with the intention of law-makers, acknowledges the churches which are larger in terms of number, and which – at least partly – possess a historical heritage. Therefore the current legislation sanctions the difference between "state-approved" larger and older communities or "quasi-state churches" and smaller communities bereft of their church status.

The combination of all these factors means that in Hungary – as compared to Western Europe or the United States – we can only talk about a "partly open religious market", in which the traditional – historical – churches are unable to perform well, owing to the above-described structural reasons.

Practical implications

One can suppose, therefore, that Hungary is in a transitional situation in more than one way in terms of religiosity, the understanding of which requires a more complex theoretical model. The disappearance of traditional religiosity supports certain elements of the secularization thesis, but we can also observe the emergence of a new type of religious attitude, one of conscious and responsible commitment to a given religious or denominational community. This latter phenomenon can aptly be explained with the theory of "religious market", but it is only partly applicable to the Hungarian religious situation. The reason for this is that after the fall of Communism in Hungary, traditional churches gained a "quasi-state-church" status under the legal guarantees of religious freedom, as they possessed great significance in society due to their historical heritage and extensive membership. Having undertaken the duty of running various institutions and therefore performing important public duties, they are forced to rely on the support of the central budget. On the part of the state there is a constant need for the symbolic legitimizing function of these churches, and the new legislation has solidified their situation, leading to the partly open nature of the religious market.

If it is true that a plural market leads to greater involvement on the level of the general population, then a limited and regulated market has the opposite effect: in a "calm" environment that is not based on competition, churches do not make efforts to keep their members and as a consequence, their membership will shrink. Historical churches have been suffering from this for some time, as the oldest generation – which used to belong to the church on the basis of tradition and not because of competition (but did not necessarily took an active part in the congregation) – disappears. In order to reach the younger generation, there will be greater competition among churches, and the less a church is able to keep its members and recruit new ones, the bigger its losses will be with the changes of generations. (Perhaps this process should be better described in the past tense – if one thinks about the current diminishing of church membership and the dynamic growth of smaller communities). Bigger churches were not forced to adapt to their environment in the past, failed to learn the language of today's people, and there is a fear that they will not be able to do so either when the competition grows, because their shrinking resources will have to be devoted to the maintenance of their current and ineffective structure.

One must ask then, do big churches really benefit from the special attention of the state? According to the theory of religious market the answer is clearly: no. One the one hand, the quasi-state-church status that appears behind the apparent liberalization of the market compromises the churches that maintain a special partnership with the state (primarily in the eyes of potential church members who appear on the consumer side of the religious market), and on the other hand, it distorts the functioning of the market – mostly in favour of bigger churches, at least in the short term. The privileged, quasi-state-church status backfires, as these "preferred" churches (which in Hungary are mostly dependent on state subsidies, rather than the support of their members) are drawn into the reassuring illusion that they will be able to maintain their structures and position for a long time, and their status is the result of their significant membership and their social influence. For them, there are fewer incentives that would encourage them to change, to engage in active mission, to address new (outside) members and to adapt to the changing social environment, in contrast to "small churches", which need to preserve the ability to grow in order to survive. While the new legislation seems to be effective in excluding the "small ones" from the competition, religious pluralism did not (and could not) cease to exist, and has provided small churches with a new role – the effective representation of some kind of religious counter-culture.

At the same time it remains a fact that big churches cannot become fully independent of the political situation, such as the attitude of current politics to churches, the use of the symbolic legitimization function, or the varying degrees of political openness towards the values represented by churches. They cannot ignore political forces that are binding upon them, either: they can only perform the duties of their system of institutions, and represent the interests of their members, their communities and those in need if they maintain relations with the political sphere. It would be irresponsible on the part of any institution to reject a relationship that entails substantial benefits, and it would result in an immediate disadvantage in the competition with rivals. Still, one must carefully consider not only the short-term benefits, but also the long-term adverse consequences.

Works cited and consulted:

Blossfeld, H. P. – Mills, M. (2005): Globalization, uncertainty and the early life course. In Blossfeld, H. P. et al.: Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. Routledge, London. 1-24.

Casanova, J. (1994): Public Religions in the Modern World. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Davie, G. (1990): Believing without Belonging: Is This the Future of Religion in Britain? In: Social Compass 37(4), 455-469.

Davie, G. (1994): Religion in Britain since 1945: Believing without Belonging. Blackwell, Oxford.

Dobbelaere, K. (2002): Secularization: An Analysis at Three Levels. P. I. E. – Peter Lang, Bruxelles.

Finke, R. – Stark, R. (1988): Religious Economies and Sacred Canopies: Religious Mobilization in American Cities, 1906. In: American Sociological Review, Vol. 53, No. 1 (Feb., 1988), 41-49.

Finke, R. – Guest, A. M. – Stark, R. (1996): Mobilizing Local Religious Markets: Religious Pluralism in the Empire State, 1855 to 1865. In: American Sociological Review, Vol. 61, No. 2 (Apr., 1996), 203-218.

Hámori Ádám – Rosta Gergely (2011): Vallás és ifjúság. In: Bauer Béla – Szabó Andrea ed.: Arctalan(?) nemzedék. Nemzeti Család- és Szociálpolitikai Intézet, Budapest. 249-262. 24

Hervieu-Léger, D. (2004): Pilger und Konvertiten: Religion in Bewegung. Ergon, Würzburg.

Iannaccone, L. R. (1991): The Consequences of Religious Market Structure: Adam Smith and the Economics of Religion. In: Rationality and Society 3. 156-177.

Iannaccone, L. R. (1994): Why Strict Churches Are Strong. American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 99, No. 5 (Mar., 1994), 180-1211.

Iannaccone, L. R. (1998): Introduction to the Economics of Religion. In: Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 36, No. 3 (Sep., 1998), 1465-1495.

Iannaccone, L. R. – Finke, R. – Stark, R. (1997): Deregulating Religion: The Economics of Church and State. In: Economical Inquiry (35)2, 350-364.

Iannaccone, L. R. – Olson, D. – Stark, R. (1995): Religious Resources and Church Growth. In: Social Forces, Vol. 74, No. 2 (Dec., 1995), 705-731.

Inglehart, R. (1977): The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Inglehart, R. (2008): Changing values among Western publics from 1970 to 2006. In: West European Politics, (31)1-2. 130-146.

Luckmann, T. (1991): Die unsichtbare Religion. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main.

Pollack, D. (2009): Rückkehr des Religiösen? Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen.

Rosta Gergely (2007): A magyarországi vallási változás életkori aspektusai. In: Hegedűs Rita – Révay Edit (ed.): Úton... Tanulmányok Tomka Miklós tiszteletére. SZTE BTK Vallástudományi Tanszék, Szeged. 297–311.

Rosta Gergely (2008): Szekularizáció vagy privatizáció? A vallásosság változása Magyarországon a rendszerváltás utáni másfél évtizedben. In: Császár Melinda – Rosta Gergely (ed.): Ami rejtve van s ami látható – Tanulmányok Gereben Ferenc 65. születésnapjára. Budapest – Piliscsaba, PPKE BTK.

Rosta, Gergely (unpublished): Religiosity and political values in Central and Eastern Europe. In: Pickel, G. – Sammet, K. ed.: Transformations of Religiosity. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden.

Sherkat, D. E. (2001): Tracking the Restructuring of American Religion: Religious Affiliation and Patterns of Religious Mobility, 1973-1998. In: Social Forces, Vol. 79, No. 4 (Jun., 2001), 1459-1493.

Sherkat, D. E. – Ellison, C. G. (1999): Recent Developments and Current Controversies in the Sociology of Religion. In: Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 25 (1999), 363-394.

Sherkat, D. E. – Wilson, J. (1995): Preferences, Constraints, and Choices in Religious Markets: An Examination of Religious Switching and Apostasy. In: Social Forces, Vol. 73, No. 3 (Mar., 1995), 993-1026.

Smith, Adam ([1759] 1982): The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Ed.: D.D. Raphael and A. L. Macfie. Vol. 1 of the Glasgow Edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith. Liberfy Fund, Indianapolis.

Stark, R. (1999): Secularization, R.I.P. In: Sociology of Religion, (60)3, (Autumn, 1999), 249-273.

Tomka Miklós (1973): A vallásosság mérése. In: Magyar Pszichológiai Szemle, 1973/1-2. 122-135.

Tomka Miklós (1990): Vallás és vallásosság. In: Andorka Rudolf – Kolosi Tamás – Vukovich

György (ed.): Társadalmi riport 1990. TÁRKI, Budapest. 534-555.

Tomka Miklós (1994): Vallás, szociológia, politika. In: Replika 1994/11-12. 181-196.

Tomka Miklós (1998): A vallásosság mérése. In: Máté-Tóth András – Jahn Mária (ed.): Studia Religiosa. Tanulmányok András Imre 70. születésnapjára. Bába és Társa Kft., Szeged. 18-31.

Tomka Miklós (2000): Vallásszociológia. (Internet book) http://www.philinst.hu/uniworld/vt/szoc/tomka_1.htm

Tomka Miklós (2002): A szekularizációról – pro és kontra. In: Lelkipásztor (77) 8-9. 282-287.

Tomka Miklós (2006): Egy új társadalmi-politikai szereplő. In: Uő: Vallás és társadalom Magyarországon. Loisir Kiadó, Budapest – Piliscsaba. 121-142. = In: Társadalmi Szemle 1998. 8-9. 19-34.

Tomka Miklós (2009): Vallásosság Kelet-Közép-Európában. Tények és értelmezések. In: Szociológiai Szemle 2009/3, 64–79.

Tomka Miklós (2010): Vallási helyzetkép – 2009. In: Rosta Gergely – Tomka Miklós (ed.): Mit értékelnek a magyarok? OCIPE – Faludi Ferenc Akadémia, Budapest. 401-425.

Tomka Miklós (2011): A vallás a modern világban. A szekularizáció értelmezése a szociológiában. Semmelweis Egyetem Mentálhigiéné Intézet – Párbeszéd (Dialógus) Alapítvány, Budapest.

The author wishes to express his gratitude to Gergely Rosta for his comments regarding the present article.