People have a will to live even among ruins, according to Bishop István Bogárdi Szabó, who, as part of a delegation, has recently visited civil-war-torn Syria. The church leader feels that the efforts of Christians in the Middle East are exemplary, and it is now our turn to help the victims of the destruction caused by the war.

In late March, a Hungarian Reformed church delegation visited both Lebanon and Syria. The delegation of church leaders and mission workers met with representatives of the National Evangelical Synod of Syria and Lebanon and the Union of Armenian Evangelical Churches in the Near East. In Syria they saw first-hand the achievements already implemented within the humanitarian, social and reconstruction projects funded by Hungarian church and state aid, projects which promote efforts for local residents to stay in their homeland. To this end, the Hungarian government had offered one million euros each to both the Armenian and Arab-speaking Evangelical communities of Syria late last year. Our church, on the other hand, has provided financial support for Sunday school programmes, a scholarship programme and the construction of a church, among other things. We sat down to talk to István Bogárdi Szabó, Bishop of the Danubian Reformed Church District and Ministerial President of the Synod to ask him about his travel experiences.

The closest most of us have ever got to understanding what war means has been listening to our grandparents’ war stories. We are generations away from experiencing what is currently happening in Syria. What did you, as visitors, experience from the realities of war?

There has been a civil war in Syria and it is partly still ongoing, although recent news have reported that ISIS has been forced out of the country. This civil war, however, has had a lot of participants. At present and for the time being there is peace, and people speak little of the war for a variety of reasons, partly because nobody likes talking about a civil war. The number of victims is staggering, reliable estimates suggest that over five hundred thousand people have been killed during the civil war, which has been going on for eight years. More than half of these people were civilians, and at least thirty thousand children are among the victims. For this is not like a regular war, fought at some distant battlefront between two armies, but a war that has deeply affected the whole country.

During our visit, the fact that we could not go anywhere without guides provided by the Syrian authorities and that we were clearly told which areas we were not allowed to enter were clear signs that we had arrived in a war zone. We were only able to go from Homs to Aleppo, which is normally a distance of only 160 kilometres, by taking an altogether 400-kilometre-long alternative route. One night we could hear artillery fire, and all along the road we saw burnt-out military vehicles, demolished cottages and complete villages, consisting of twenty-thirty houses, destroyed by bombs. Apart from a handful of districts that have been spared, cities are also in ruins, because they have suffered serious attacks ever since the start of the civil war. They have been occupied by various forces, suffering bomb and missile attacks. Half of Aleppo is in ruins, Homs has been completely destroyed, the only city we have seen that has suffered relatively minor damage in comparison is Damascus, due to the fact that ISIS never managed to actually enter the city, they only surrounded it. Still, in the outer districts of the capital, there were signs of damage caused by missiles. In my estimation, it will take generations just to clean up the ruins.

And the wounds of society must go even deeper.

Such wounds are extremely severe. Everybody strives to achieve reconciliation, which is a basic condition for survival, for people do want to survive, they have a will to live, and they are trying to rebuild their lives amid desolate circumstances. Those who have left are not really willing to return, as there is no home for them to return to. Hundreds of thousands of buildings – apartments, houses, public buildings, schools and hospitals have been demolished.

Speaking of reconciliation: Muslims and Christians have been able to live in peace for centuries in the Middle East, but in Syria everything got turned completely upside down. Who are the parties that need to find reconciliation with each other?

We, Westerners – and in this scenario I count as a Westerner myself – naively believe that the fact that they were able to co-exist for so long just happened to be the case. The compromises they used to have were always very delicate, carefully constructed and closely followed, compromises that were very much active and effective. And it was only to be expected that when this centuries-old balance of numbers, influence, wealth, as well as national and local politics gets disrupted, the whole system would collapse. Everything has changed, as a significant proportion of the Syrian population has fled the country, and there is no way to know who will eventually return and who will not. In the major cities there used to be Christian, Armenian, Greek, Kurd quarters, all of which have been destroyed, therefore certain territorial revisions can also be expected in order to ensure peaceful co-existence in the future.

The ideology of the Islamic State aimed to destroy the current civilization. This new caliphate proclaimed that they would be building a new civilization on the ruins of the old one. They did their best to destroy everything that belonged to Middle Eastern civilization, from Christian quarters and mosques to Muslim holy places and ancient or medieval treasures. We saw a Christian church being reconstructed after suffering a missile hit, and next to it was a mosque in ruins, so the destruction was aimed at everyone without exception.

So the task is now to start rebuilding the system of compromises that had been constructed and maintained for 1200 years. The peaceful co-existence of neighbours is an everyday art form, so they are seeking ways to reach reconciliation. Everyone has suffered losses and injustices; everyone has lost someone; everyone has been involved in the conflict in one way or another; everyone had to make a stance at some point. This is one of the most terrifying aspects of civil war, the fact that you cannot stay neutral. Even pacifists took a stance by choosing pacifism; even those who were only protecting their own lives took a stance in some way. Even if the war ends, there is a long road ahead of Syria.

We also know from reports that locals appreciate very much not only the financial and moral support they receive, but also the fact that we actually visit them at the site of their tragedy. Why is personal presence so valuable in such a situation?

This is truly so. It was deeply moving to see how much they prepared for our visit. It almost felt like we were participating in a wedding reception. We are in the period of Lent, which they observe even more so than we do, therefore they only eat meat once a week. And yet, during our visit, they served lavish meals every night, while at the same time in Aleppo we witnessed the endless queues of people hoping to get some meat. Even amidst their poverty, they wished to welcome us with the utmost respect, which was really moving.

And they told us the reason for such a warm welcome: they have been receiving plenty of nice messages and support, and even more promises. They did not hide the fact that the amounts they have been offered are significantly more substantial than what we, Hungarians can provide. And yet, we are almost the only ones who dare to actually pay a visit there and participate in their everyday life. They could show us their former houses, schools, demolished churches, and this personal presence – the fact that we do not merely look at their misery on postcards and photos, but actually gain first-hand experience – means more to them than anything else, and they received us with more love than we could ever deserve.

For those who have never heard about these communities, it is rather surprising that there are people of Evangelical faith in Syria and Lebanon. What is an Evangelical Arab person like?

As we all know, one can find Reformed, Evangelical people all over the world. The origins go back to the 19th century, when Syria was under the rule of a British protectorate, and during this time representatives of the Western world, including missionary workers, appeared in the region. Today’s churches have their roots in Western Presbyterian-Evangelical missions that took place in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

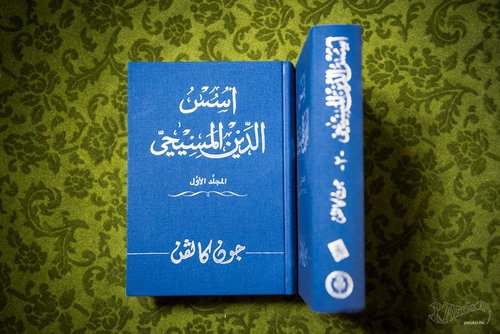

They have a lot in common with us, although their liturgy and robes are more Anglo-Saxon in nature, following Scottish or American Presbyterian styles, but their churches are white, just like ours, and the structure of church service is almost identical to ours, apart from a few items. They primarily sing Anglo-Saxon hymns, but we have heard Armenian and Arabic Evangelical songs sung in each community, respectively. I have brought back a copy of Calvin’s Institutio, which has just been translated into Arabic. Their mentality is also similar to ours, as they represent an insignificant minority even within the Christian community of a predominantly Islamic country. Ancient Eastern Christians – Syrians, Greeks, the Old Catholic Church and others – are firmly established in the country, they keep preserving their traditions, but the Evangelical community is a novel element within Christianity in the region. There are, however, fewer confrontations, even based on language, within the Christian community than in Hungary, for obvious historical reasons. They pay more attention to each other, putting up a unified front.

Armenians fled to Syria from the threat of genocide in the Ottoman Empire at the beginning of the 20th century, and now they are faced with this current trauma. As Christians, what is their attitude to the events unfolding over the past years?

Armenians are in a very difficult position since they are grateful to Syria for having taken them in during the Armenian genocide. They are grateful to the Arab and Muslim community because they, as a community of fleeing Armenians, were welcomed and were able to create their own spaces within the community. They constituted a well-respected group within pre-civil war Syrian society. And now they have found themselves drifting helplessly in a country torn by a civil war. Whose side should they choose, who should they praise, how should they express that they would very much like to stay here? Although many Armenians from Syria have already left, their community is hoping for their return, so their wish to stay in Syria is still true. Perhaps that is why Armenians are one of the most active parties in the reconciliation process. The fact that they have only been there for a century, their position as former refugees and an absolute minority, as well as the fact that they have no real stake in taking sides in internal Islamic matters have all put them into a position of mediator.

What situation are church leaders in, what are they struggling with? What did they tell you about the lives of congregation members, of the families still living there?

Most church leaders have stayed in the area, although there might have been a pastor who left his congregation to go to the West, and has been replaced by a retired pastor. Those who are still there are definitely promoting reconstruction. When we saw what they have started over the past two or three years, since the gunfights have ceased, I had a real sense of guilt, feeling that we are nothing but a crippled and complacent European “pensioners’ club” compared to their level of activity. The amount of energy, inventiveness and creativity with which they have been rebuilding their community is unbelievable. They are most worried about the youth, whether this generation will ever see a future for themselves in Syria. There are impulses from Western Europe, encouraging people to leave, and even opinions that Syria is over and done with, that there is nothing to be done there. They, on the other hand, know that it is not all over, and that there is something to be done there. So while they receive a lot of support from the West to rebuild their churches, hospitals, religious schools and their lives in general, the same Western world is also a source of attraction and appeal.

The situation of Christians used to be less volatile during the former reign of President Hafez al-Assad. To what extent can it be felt that they have since become persecuted?

It is no exaggeration to say that they were already persecuted during the civil war, as one of the military tactics of ISIS was to occupy Christian quarters first. This has resulted in martyrdom at times, for example in Homs we visited a Jesuit monastery, which everyone had abandoned during the chaos of war, except for an elderly Dutch Jesuit man. When the terrorists entered the building, they told him to leave. He replied that the monastery was his home, he had been living in Syria for sixty years, serving this country and this nation. He was shot and killed on the spot, in the yard of the monastery. So there have been atrocities against Christians because of their faith, mostly because the terrorists invaded Christian quarters. If the government or a rival militia, or any group involved in the civil war tried to force the terrorists out, they bombed the Christian quarter first. If we can talk about proportions – which would be unfair –, it is Christian districts that have suffered the most due to this calculated war tactic.

More and more hearts in Hungary are touched by the extent of the persecution of Christians. What is your message as a church leader to us within the body of Christ, when we keep hearing such news? What is our duty, what should we do?

Let me recount three examples from the twentieth century that we, Hungarians should take to heart. After the First World War, several children who had lost one or both of their parents in the war and were practically skin and bone were taken to the Netherlands or Switzerland for a few years to have their good health restored. Nobody forced their benefactors to take on this task; they did so because they were Christians. By the time the Second World War ended, roughly one-third of Hungarian Reformed church buildings had been damaged or utterly destroyed. In about four-five years these churches got rebuilt, and not from the donations of desolate, surviving Hungarians, but from those provided by our WWII enemies. And then after 1956 for a long time I held on to a large cheese box with a red cross on it, and the caption ‘Donation of the USA’. It was not something that necessarily had to be done. I can still remember that when I was a child, during the years of Communism, we regularly had Christian visitors who supported us, coming from the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany.

Since we, Hungarians, spent the whole twentieth century getting help from somewhere, receiving donations, often delivered in person, it is our duty to give what little we can spare to Syrians or persecuted Christians anywhere in the world. Let me mention a specific example. There is a church in Aleppo where a medical facility has been set up, where the doctors who have stayed behind volunteer three or four hours each week, free of charge. The church also operates a pharmacy, and if a person goes there to be examined and receives a prescription, they can get the prescribed medicine for free. It is not a huge sacrifice to send a box of aspirin or some antibiotics, or the price of such basic medications. Just think about the amount of medicine we throw away when it expires or is no longer needed. And there are places in the world where a group of Christians open the doors of a doctor’s office for other Christians and also for Muslims or anyone else, and the donations their Western brothers and sisters collect for them are spent on providing medicine for the patients.

During your visit, what had the greatest impact on you?

I have received a multitude of impulses, and I need some time to process them all. I often say it is all right as long as there is peace. And these days I say, it is all right as long as there is no war.

Interview by Ágnes Jakus

Translated by Erzsébet Bölcskei

Photos by György Feke, Tamás Füle, András Harmathy, Balázs Ódor

Originally published on parokia.hu