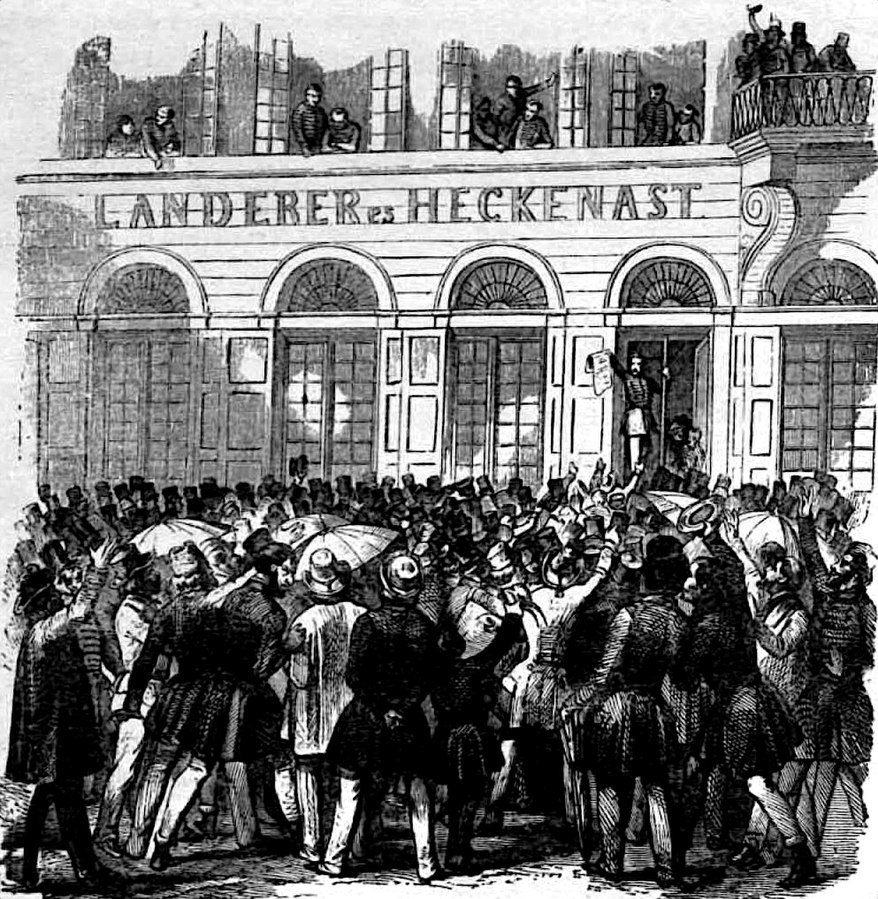

On Monday Hungary is celebrating the 173th anniversary of its 1848-1849 revolution and war for independence. 15th March, starting date of the 1848 Revolution against the Austrian Empire, marks the Revolution and Independence Day, which is one of the most widely celebrated National Holiday in Hungary. It is also a celebration of youth and Spring, but after all of freedom and liberties. On this day even children recite the poet of the revolution, Sándor Petőfi and the refrain of his often quoted poem, the Nemzet dal (National Song): "Shall we be slaves or men set free?" Remembering that the issue of freedom and liberties is just as crucial and relevant as in the days of the revolution. One of the most important expression of the liberties we hold high today is the Freedom of Press. Petőfi renamed the Hatvani Street to Street of the Free Press (Szabad Sajtó utca) and the crowed seized the Landerer Publishing and Press company, located in that street. This is the place where the famous 12 points were first printed. They summarized the reformers’ most important demands that served as basis of the so called April Laws modernizing the Kingdom of Hungary into a parliamentary democracy, nation state. Freedom of press and the abolition of censorship was the first claim vindicated by the revolutionist. Thus, 15th March became also the memorial Day of the Freedom of the Press in Hungary in 1990, right after the political changes and the liberation of the country.

The crowd captured the Landerer & Heckenast printing house, where they printed the 12 points and the National Song. Thus 15 March became the memorial Day of the Freedom of the Press in Hungary.

This year we celebrate the day of the Revolution in publishing the reflection on this crucial and too often challenged ‘revolutionary’ principle. Thoughts about freedom, press and responsible journalism are offered by Zsuzsanna Farkas, editor-in-chief of reformatus.hu, the official website of RCH.

15 March 1848 is one of the major milestones of Hungarian history, commemorated with pride year after year. Less attention is paid to the fact that, since 1990, 15 March has also been the Day of the Hungarian Press. As a journalist, I am also proud of the fact that the first item on the 12-point list of demands of the March Youth was: “We want freedom of the press, the abolition of censorship”. It was in the spirit of this demand that the first products of the free Hungarian press were printed: Petőfi’s ‘National Song’ and the 12 Points, and on 11 April the sovereign signed into law Act XVIII of 1848 on Freedom of the Press – but what does this all mean to us today? Does it even make sense to talk about freedom of the press in the age of new media, when anyone can become a content provider, and information is available without restriction? In my experience, it actually increasingly does. Dialogue is most needed in situations when anything – and its opposite – can be published freely.

Even today, responsible journalism is able to highlight societal problems and processes and has the ability to warn readers. With the help of the internet, it can do so at an ever faster pace and to an ever wider audience. For this very reason, however, we cannot discuss the press without mentioning communication, media and society as well: the evolution of the media is influenced by its contemporary society, and in turn, members of society are influenced by the media. Over the past few decades, our communication with each other has undergone a change: due to digitalization, opinions have become much more far-reaching and are now able to provoke much stronger emotions. At the same time, media processes should be evaluated from an ethical point of view, its operations should be in line with moral norms – and laying the foundation of such norms and enforcing them is a common debt we all share. Furthermore, the majority of the most significant problems of our age are issues that can surface in the media, and public thinking can be transformed as a result.

Street Plate of the Free Press street in Budapest

It is important, therefore, to first take a step back and interpret what it really means to talk about freedom of conscience and freedom of speech. We must, first and foremost, consider the responsibility that with our communication we must not deliberately offend the personal convictions and worldviews of others, but at the same time we must stand up for our own values and represent the truth. Truth, however, for the most part, is not objective – and when examined, it can lead to conflicts of opinions, grievances, perspectives and interests. For this reason, many say that there is no such thing as freedom of the press: when we represent one side or the other in various questions, this freedom is infringed upon. From a certain point of view every press publication is dependent on something or somebody, and our only freedom is choosing what or who we depend on. This is an eternal struggle of ideas, ethical questions and stories, which is not easy even for a church journalist – although one is supported by solid foundations: “All you need to say is simply ‘Yes’ or ‘No’; anything beyond this comes from the evil one,” reminds us the Gospel of Matthew (5:37), so that we as journalists, Christians and church members should strive for direct, true speech and utterances. In this process the oft-forgotten power of dialogue gains more weight, as well as the freedom of voicing opinions with an awareness of the impact the words we utter have. And we need dialogue and clear expression more than ever, since we have to express our opinion on grave societal issues as well. If we are not authentic as Christians when it comes to such issues, we can hardly expect others to see us as authentic when spreading the good news of the gospel.

Although the world never stops changing, I believe that the press does not merely inform people and tell stories, it is also a branch of power: its aim is to keep a check on the powers that be, and to represent the voiceless. To become a voice where there is forced silence. What, then, does freedom of the press mean to me? An ideal worth fighting for – even if it can never exist in its imagined perfection. It means being able to tell the stories that help Christianity go beyond us. It means the courage to ask questions, and to represent and bear witness to the truth that redeems.

Originally published in Reformátusok Lapja, the Weekly Magazine of RCH. Translated by Erzsébet Bölcskei.

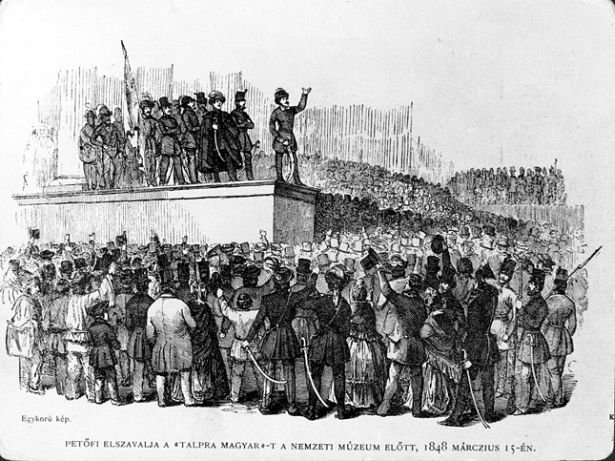

On the 15th March the poet Sándor Petőfi, as one of the leaders of the revolution recited his mobilizing poem National Song also at the National Museum where 12 points were also read out.

What the Hungarian nation wants - in 12 Points

On the morning of March 15th, 1848, thousands of revolutionaries marched around the city of Pest, declaring an end to all forms of censorship, while reading Sándor Petőfi’s National Song and the 12 points. After they printed Petőfi’s poem together with the list, a mass demonstration was held in front of the newly built National Museum. When the crowd rallied in front of the Imperial Governing Council, the representatives of Emperor Ferdinand agreed to sign the 12 points.

Let there be peace, liberty and concord.

- We demand the freedom of the press, the abolition of censorship.

- Independent Hungarian government in Buda-Pest

- Annual national assembly in Pest (by democratic parliamentary elections, the abolition of the old feudal parliament which based on the feudal estates)

- Equality before the law in civic and religious terms (universal equality before the law)

- National army

- Taxes and public dues (universal and equal taxation)

- Abolition of the Aviticum (Aviticium was an old feudal origin obsolete declared that only the nobility could own agricultural lands)

- Juries and representation based on equality

- National Bank

- The army must take an oath on the Constitution, to send our soldiers home and take foreign soldiers away

- Setting free political prisoners

- Union (with Transylvania)

Equality, liberty, brotherhood!