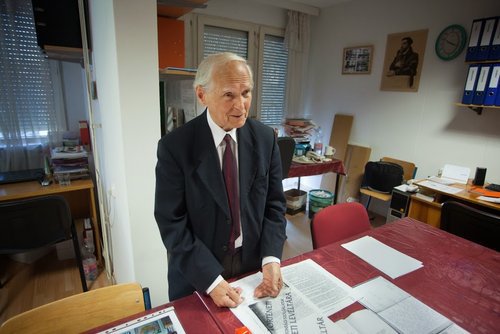

A lot of people know him in the church. It's no wonder, because he is always on his way, and although he has many tasks, there is not an important church event where he is not present. In remembrance of the 1956 revolution we spoke with Dániel Szabó, who was recently awarded the anniversary medallion of the Debrecen Reformed College on its 475th anniversary. We asked the former lay president of the Cistibiscan church district, who turned 80 this year, about his memories from the '50s.

Electrician, hotel receptionist or Reformed pastor? Which one are we talking about when we are talking about Dániel Szabó?

All of them. In my work book, next to the first and second, it also said professional driver. Temporarily I was a mason's apprentice, brick-maker, worker in a vineyard and livestock breeder, too. All of these were a part of me, and anywhere I've was, I saw my environment as a place of mission. For example, thousands of workers worked in the factories at Miskolc, and as a theology student I returned there during the summers.

The employment record book, or so-called "work book," was an official personal document listing the owner's employment status and complete work history over time. Socialist countries saw virtually full employment, an artificial construct, and to have no official job was a crime.

Mission among the working class in one of the model factories of developing socialism?

It's a fact that no pulpit waited for me in the factory but the noise of tool bags and air thick with the dust of cement. But in this huge factory, in its hidden nooks in transformer house or on the top of the electric poles, personal relationships couldn't be monitored. I'm not exaggerating if I say that a kind of community of love was formed between us. When I returned back among my coworkers every summer, they welcomed me and whispered to me who I should be careful around. I was working with political prisoners for a while. I was the head of a brigade with 8-10 people. It was really elegant company with appreciative, intellectual people. I wouldn't have dared distract them. "Could you be so kind to hand me a screwdriver?"- I asked to one of them. "Don't trouble yourself, I'll go down the ladder"- I said to another. When their overseers were around us, I put up a sign a warning sign for high tension that didn't allow entrance, so that we could talk to each other.

Dani Szabó's "Free People half hour"?

Maybe it's better to say community building in factory conditions. Once my father, who was deprived of his pastoral robe, was forced to rebuild a vineyard field devastated by the farmer's co-op. We bought specialized books and received workers, and in this way we set out to do our tasks without the smallest hope of profit. I looked at the workers and the vineyards as a congregation. It reminded me of the gardens in the Old Testament planted by God, and I was thinking, how could it be that even though we were panted as fine grapes we have become the sprouts of a foreign grape. I saw that the condition of the garden is also our condition, and God wants to replant the destroyed grapes, prune the wild sprouts, and in this way, we renew and produce fruit.

"Free People 30 minutes" was an expression for the obligatory daily political "discussion" at workplaces, where people were confronted with the official standing points (Propaganda) of the ruling Hungarian Working People's Party. They usually quoted and reflected the "Szabad Nép" (The Free People), the central organ of the Party. In 1956 it was succeeded by the Népszabadság (People's Freedom), which was the mouthpiece of the communist Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party until 1989.

Your dream was to become a Reformed pastor, but you were expelled in 1956 from the seminary in Debrecen. What happened exactly?

My father was a pastor of a revival community, that's why he was immediately against the dictatorship. When I came to theology, he had already been suspended from his duty in Hejőcsaba, like my godfather, József Benke, a pastor from Hejőpap. Therefore my family was strongly exposed politically. When I got to Debrecen in 1952, this tension was apparent among the professors too. On the national church level there was a big debate about the conversion of private farms into farmer's co-ops and the use of propaganda in sermons, and we supported the professors and pastors who stood up in protest against these issues. Initially under the protection of our teacher's wings and our good grades saved us from the consequences. Some of them were arrested because of their thoughts and some of us wrote a letter to the bishop, saying that if anything bad should happen to them, we considered him responsible. It seemed to be the end of our studies, but the revolution of 1956 interfered, and brought with it a turning point in history. I remember that my professor grabbed my arm in the corridor and told me: "Dani, I can't bear to think that you are fighting on those frontlines, where we grown men, should bleed to death. It keeps me up at night that you, the future generation, will die in this horrible struggle." He saw it well, because we were not only their students, but their brothers-in-arms.

They could not avoid their destinies...

After the revolution I wrote an essay about the Swiss theologian, Walter Lüthi. He revealed the impact of Nazism in his preaching; that later the activity of the church during the Communist dictatorship was considered a prophetic view. The study with my other assertions pointed out this issue, and it kind of touched the church leadership. Before my final examination they suspended me for one year, and after this forced break I would have showed a new essay that my life took an important turn. However, I wrote about the ethics of János Arany, warning about the fact that the current system made the new generation existentially dependent by breaking their backbones, and them making moral. It exploded like a bomb: at the final examination they announced in front of the young theologians, that I was expelled once and for all with no hope of becoming a pastor, along with two of my friends. There were three reasons listed: we were rebellious, and our views were unacceptable, and there was no hope that they would change. After this, the case was taken over by the police. We were arrested, but I couldn't be put in prison without concrete evidence. It turns out that my essay was taken away and hidden by my beloved and respected Dean, Endre Tóth.

How do you recall the few days of the revolution of 1956?

We heard the first rifle shots in Debrecen. As we learned what was happening and that they were looking for volunteers to carry food, we immediately applied. From that time I was commuting in military vans with my friend between the capital city and Debrecen: we delivered food there and coffins on the way back. It was a tragic experience to see old peasant women cry weakly and sit on their sons' coffins. I sadly stopped over many burned bodies of Russian foot soldiers next to burned-out tanks. At this time I asked myself: why did you come here? And I was sorry to think, their mothers were wasting time waiting for them to return home... I do not think it is treasonous to feel this, even today. We continuously walked around the city watching the scene, and even I sawed-off a piece of the Stalin statue. During these days, we felt that our nation had become a large family. I was surprised at the moral exhilaration that made the broken show-windows of jewelry stores and the collection boxes untouchable with this message: "The purity of our revolution allows collection for the relatives of our fallen." I wrote my last experiences in an article of a revolutionary newspaper in Debrecen, and reprimanded the people - many times self-appointed voices, who wanted to dismiss, urgently, the church leaders – that it is not an option to take away resources from the broken "church windows," we have to wait patiently until congregations distribute the portions among us equally. We delivered news between the two theology schools, and transmitted the post of the professors. We were at the theology in Budapest, where László Ravasz was asked to undertake the title of bishop, and furthermore asked to give his radio speech.

László Ravasz was the former bishop of the Dunabian church district but was forced from his position in 1948 when the Communist government began the "systematization" of churches. During the 1956 uprising, the "Movement for Renewal of the Reformed Church" called for the resignation of current church leadership and the reinstallation of Ravasz to his former position. He gave a radio speech on 1 November, the same day Prime Minister Imre Nagy declared the neutrality of Hungary and called on the United Nations for assistance without effect. You can read Ravasz’s radio address here.

During the decades of the Kádár era you worked as a receptionist, and after that you retired with only a small pension. Did you feel indignant toward the church or your ill-wishers?

My father taught on the principles of the book of Proverbs, that we must not despise our parents, even if they grow old. He said: though our Church is in an exhausted condition, she is our spiritual mother; here we got to know the Gospel. We got a huge gift from her, that's why we have to be grateful, even if she treats us desperately nowadays. It warns us to the fact that for a Christian it is not enough to read the Bible and pray, but what is important is spiritual generosity, which means making sacrifices, the ability to lose, forgiveness and eternal hope. He believed that our family at least had to stay honorable, even if we don't experience the same from other people. That's why he forbade being abusive, or speaking disrespectfully about our adversaries.

But after all, there wasn't any bitterness inside you because you could not be an ordained pastor?

I received so many good things and opportunities to serve from God, and he made his presence and guidance in my life so apparent. That's why there is no complaint or bitterness in me about anybody and anything. Side by side with my receptionist life, another life evolved: with western support I was able to organize a smuggling network beyond our borders – we delivered food and Bibles. In the Soviet Union, I helped Protestant pastors returning from the Gulag as an agent of the Dutch church. After the regime change, I worked as a lay president, and was the main supporter helping several schools and diaconal homes running in the Carpathian Basin. Today I'm a representative of small Protestant churches, involved in the mission among Roma, and I am an active member of the Hungarian Reformed Elder's Association. Why would there be bitterness inside me? I wouldn't have had these opportunities to do so many things as a local pastor. God made great things. I was able to see empire sank and collapsed, and saw how enemies of the church became God-seekers, at times supporters, possibly even friends. We were living in historical times, and although I'm just a grain of sand, God after all used me in these events. Who am I to argue with God? All glory is his, mine is the uncertainty of whether I did everything I could.

Dr. h.c. Dániel Szabó was born in 1933 in Hejőcsaba near Miskolc. As a pastor's son he was not admitted study medicine, so he became an electrician and after that, studied theology. Though an excellent student he was not allowed to be a pastor. He worked as a concierge and continued serving in the church, especially among Roma. He was given an honorary doctorate by Montreal University and the Protestant Theological Faculty in Cluj.

He served as lay president of the Cistibiscan Church District for two terms and he is president of the Reformed Elder's Association. He also presides over the Hungarian Evangelical Alliance and the Wycliffe Bible Translators' Association. He is an honorary professor at the Theological Academy in Sárospatak.

Written by: Sándor Kiss; translated by: Timea Túri

Originally published by: Reformátusok Lapja 2013/42

Portrait: Krisztián Sereg

Cover photo:MTI