We have visited the 2000-year-old Christian memorials of Syria’s capital, as well as its Armenian and Arab-speaking Evangelical communities. Our brothers and sisters experienced the spiritual journey of Paul during the years of war: they gained a new kind of sight amid their suffering that sets an example for us as well.

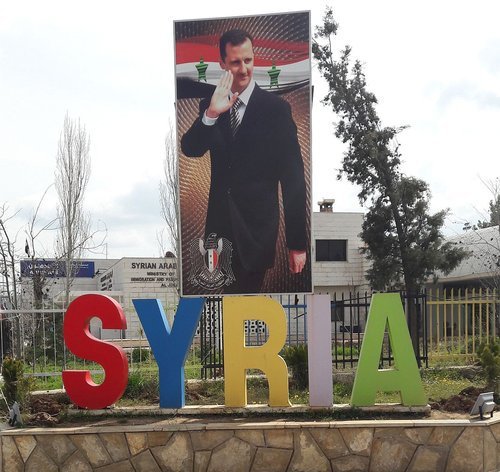

Upon crossing the Lebanese-Syrian border, we are welcomed by the sun shining down on the snow-covered, 2800-metre high Anti-Lebanon Mountains as well as on the giant portrait of President Assad. As we descend into the valley of Halboun through a road carved into a cliff, the sky gets increasingly overcast, and by the time we approach the capital, raindrops blur the landscape. As if nature itself was mourning the cities and villages destroyed by missiles.

The road to Damascus is filled with signs of destruction and utter silence. We drive by half-demolished settlements, buildings covered in bullet holes and empty streets – the only noises come from the drizzling rain and the roar of the engine. Our guides have also fallen silent, it is only later, having returned home, that we realise that these were the ruins of Douma, a city near Damascus. Douma had been occupied in 2012 by opposition troops, and it took five years and violent battles for government troops to regain power; it is said they even resorted to chemical warfare. A similar fate befell several suburban areas of the metropolis, which lies in an extensive oasis, during the civil war that has been going on for eight years. The road to the oldest continually inhabited city seems to be paved with anger and hatred – just like two thousand years ago.

Preserving Hope in the Middle East

‘We are acutely aware what it feels like to receive help in troubled times, and now it is our turn to help our brothers and sisters to preserve hope during this difficult period,’ said Bishop István Bogárdi Szabó at the signing of a Memorandum of Commitment with the Armenian and Arab-speaking Evangelical communities. At the end of March, a leadership delegation of the Reformed Church in Hungary visited congregations of their Evangelical partner churches in Lebanon and Syria, seeing first-hand the projects implemented with the help of funding from Hungary.

“Why do you persecute me?”

‘If anyone asks where they can find us, I always answer that our address is in the Bible,’ says with a smile on his face Armash, the Armenian Orthodox Bishop of Damascus. Their church and school are located at the edge of the old town, next to the city’s wall, on the so-called ‘Straight Street’, which is mentioned in Chapter 9 of Acts. According to locals, Saul – who would later become the Apostle Paul – was led by the hand to Damascus through a nearby gate. This happened after Jesus Christ had appeared before Saul, a man filled with hatred towards Christians, and Saul lost his sight. His malevolent intentions were thwarted by the question “Why do you persecute me?” In that case, violence stayed outside the walls of the city.

We are warmly welcomed by the Orthodox church leader, who offers us coffee and a tour of the church. The bishop, who completed his doctorate studies in Germany on liturgics, says that they experience the notion of oecumene in a different way than it is felt in Europe: ‘We truly believe that the invisible church is one, and we are all members of it. Therefore we consider the Armenian Church to have two branches, an Orthodox and a Protestant one.” We find it easy to believe him.

It is revealed that before the war broke out, the two communities had been in the process of finding points of interconnection and ways to undertake joint service; they regularly participate in each other’s worships. Many of the flock have fled Damascus and the surrounding region since the years-long armed conflict began. The community Bishop Armash is in charge of has only four thousand members at present, and the local Armenian Protestant community is also very small, but they do their best to help those in need in the area, trying to preserve their Christian and national identity in a double minority position.

“Who are you, Lord?”

A few blocks away, the school day has just ended in the school of the Armenian Evangelical community. The teachers wait for us patiently, sitting and talking in the shade, while we marvel at nearby shop windows. People must have waited for night to fall in a similar fashion two thousand years ago in Damascus. Our partner church bought a traditional house in 1950, which was turned into a school building. The rooms opening to the yard used to house families, but since then, generations have been taught here the three Rs: reading, writing and arithmetic.

The school, where 250 children study, is soon to be renovated with the help of funds provided last October by the government of Hungary. The desks are rather worn, the walls need a new coat of paint, and the gas fireplace is also quite old – a member of our delegation even remarked that the place reminded him of his own elementary school days, except they used coal for heating. But that was over fifty years ago, so comparing it to a present-day setting is quite telling…

‘Please never forget that what you are doing is one of the most important tasks,’ says Bishop Bogárdi of the Danubian Reformed Church District to the teachers in the yard. ‘Not only do you open children’s eyes to the world, but by teaching them to read and write, you also open their lives to the Kingdom of God.’

„Here I am, Lord”

The moderator of our other partner church, the Arab-speaking National Evangelical Synod of Syria and Lebanon (NESSL), shares the sentiment that education is the key to Syria’s future. ‘Buildings are easy to renovate, but the wounds of the human heart are a lot harder to heal,’ says Butros Zaour, pastor of the Damascus church of NESSL, while we are drinking yet another cup of delicious coffee in the community hall of the church, which has been restored after suffering missile hits.

The first Arab-speaking Protestant people appeared in Damascus in 1866, and over the past 150 their community has become the second biggest church in the country (second only to the community in Latakia, a port city we visited in 2017). Back in the day, they built a church together with their Armenian brothers and sisters of faith, which later became the property of the larger community, but the Armenian Evangelical community can still use it: they, too, hold their church services here.

Radical groups try to gain power through religion and violence – the truth of which has not only been felt by Christians in Syria over the past few years, but by Muslims as well. Our hosts take us to the Umayyad Mosque, which is one of the seven wonders of the Arab world, where the head of John the Baptist is said to have been buried. After the Friday prayer, we are greeted by a good friend of the moderator of NESSL, who also happens to be the leader of the most important Islamic religious centre. Earlier, he was abducted by Islamic extremists, and one of his ears was cut off, because he refused to support the ideology of the extremists.

‘Fear, destruction and hatred are not native to Syria, these were imported from abroad,’ our hosts claim. During the years of fights, they never ceased to pray for their enemies, even when they were being attacked, and now they are striving for reconciliation. It has always been natural for Muslim and Christian children to sit next to each other in Evangelical schools, but since 11 million people have fled their homes, the proportions have changed, and the majority of children are now Muslim – and they are taught not only reading, writing, arithmetic and foreign languages, but also forgiveness, tolerance and peaceful coexistence. The situation is the same in their Sunday schools and at church events. A good sign that their efforts are not in vain is the fact that their worship service is broadcast on television.

„… he could see again”

Our Damascus trip ends in the house of Ananias, a disciple of Jesus and the first bishop of Damascus, whose house is believed to be several metres below today’s street level. Through one of the now-familiar internal yards we descend upon a staircase to a stone building, which has been transformed into a church by Franciscans. It might have been here that Ananias had a vision about Jesus (Acts 9:1-30), uttering the words: “Here I am, Lord.” And Jesus told him: “ ‘Go to the house of Judas on Straight Street and ask for a man from Tarsus named Saul, for he is praying’ ”. As we all know, Ananias was reluctant to go, as he had heard about how much harm Saul has done to the followers of Christ, but in the end he complied, went to Saul and told him: “ ‘Brother Saul, the Lord—Jesus, who appeared to you on the road as you were coming here—has sent me so that you may see again and be filled with the Holy Spirit.’ ” The Bible also relates what happened afterwards: “Immediately, something like scales fell from Saul’s eyes, and he could see again. He got up and was baptized, (…) he began to preach in the synagogues that Jesus is the Son of God.”

The peaceful silence of the chapel amplified in me the words uttered by Károly Fekete a few hours before. The Bishop of the Transtibiscan Reformed Church District, upon seeing the testimony and wound-healing work of the local Christians, who have been plagued by both the civil war and by their minority position, said: ‘It is enviable to see that despite the horrors you have experienced, your eyes have opened up, you have gained sight and not only do you wish to right the wrongs of the past, but also aim for new beginnings. Your exemplary behaviour also gives us strength to defeat our own weaknesses.’

Written by György Feke

Translated by Erzsébet Bölcskei

Photos: Tibor Ábrám, György Feke, András Harmathy, Balázs Ódor